I didn’t need the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to release their latest climate assessment report to know that climate change is here now, or that it will only get worse. Did you?

For years – well before last month’s Heat Dome – Indigenous and settler communities in Canada’s dry-belt have watched as the landscapes around them change. When the web of Interior watersheds flood during the spring freshet, or during ensuing wildfire seasons, it can feel like BC’s rural communities are often left to fend for themselves during back-to-back climate calamities. We didn’t need the IPCC to tell us that our governments weren’t doing enough to prevent the worst of it.

Last spring, I wrote about how people along the Bonaparte River came together to provide mutual aid, offer advice and help their friends along the river’s edge during 2020’s record-flood season. Although my experience this year was far more traumatic, coming face-to-face with the impacts of climate change has made all of this feel more personal, and it has me wondering:

How bad do things need to get before our governments treat traumatic climate events like the emergencies they are? How hot is too hot?

Cumulative impacts & climate worries

Our place (on the border of Secwepemcúĺecw and Nlaka'pamux Territory) is situated in one of the only desert landscapes in Canada, part of a unique collection of shrub-steppe microclimates where desert hallmarks like rattlesnakes and black widow spiders dwell in a backdrop of sagebrush and cactus. The drive from the coast takes you from rainforest to grasslands in less than four hours, and it doesn't feel like anywhere else.

Nearby Elephant Hill is now a light green with regrowth after the 2017 wildfire ravaged its silhouette from trunk to backside. Local rangelands specialists and Indigenous land-use experts (like Secwepemcúl'ecw Restoration and Stewardship Society) have made a major impact, but it still doesn’t look the same. The flat-topped hills and hoodoos are now cut through, and expansive grasslands now feel both sci-fi lunar and sun-beaten apocalypse.

Even a settler like me can see how much the area has changed. Fewer salmon are seen spawning in the Bonaparte River, and the steelhead no longer swim past you while you take a dip at the Thompson River. The public can't access the Ashcroft Slough anymore since the Terminal cut off access. Trucks trundle past at a regular pace, filled with livestock, farm equipment and fertilizers. From the hill behind our house, the valley that used to look like it went on forever up the Thompson now looks like an open-pit mine filled with parked railcars and massive storage facilities that make up the Ashcroft Terminal (the second largest inland rail port in Canada.)

The trains never stop, ever – there is a constant stream of rail traffic, no matter how hot, no matter how high the risk of ignition. We worry about what would happen if a train were to derail and fall with all of its toxic chemicals into the river, or send a spark into an unkempt ditch, but all we can do is hope for the best.

Close to home

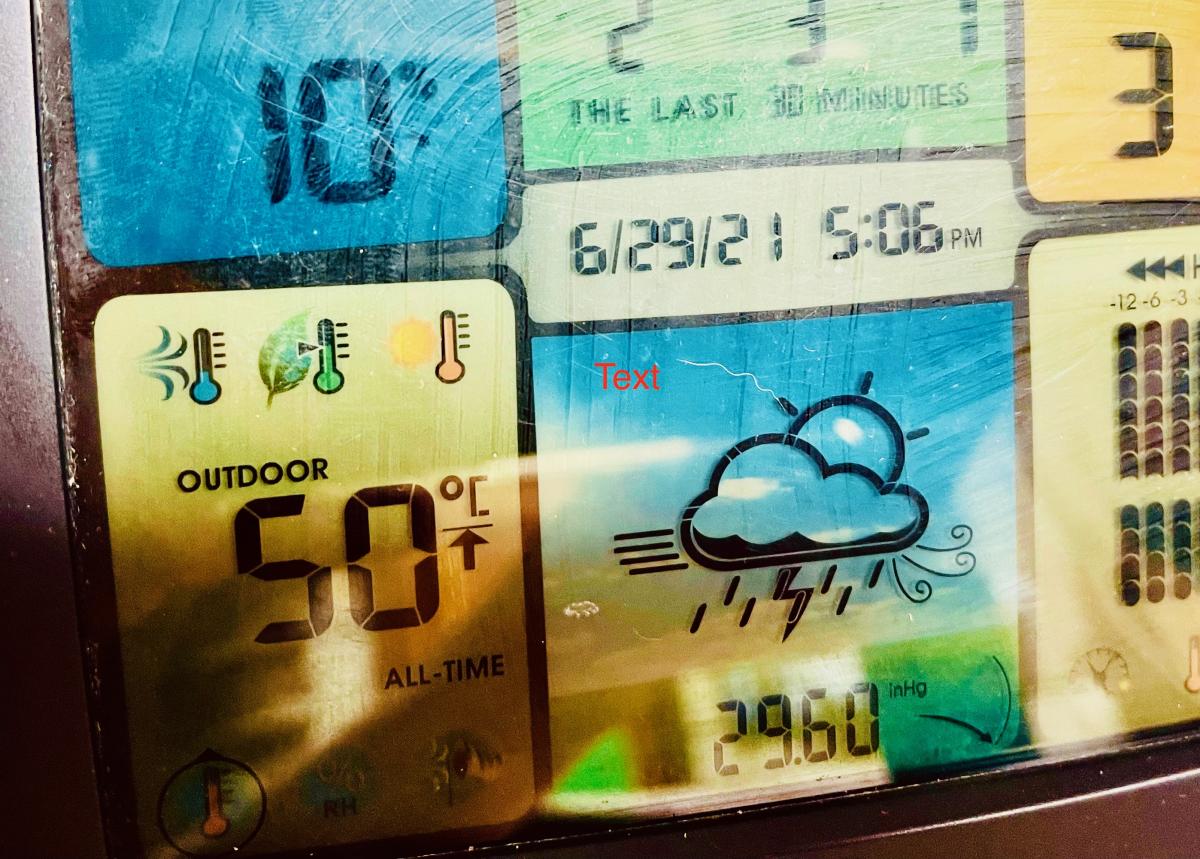

The day before the village of Lytton burnt to the ground on June 30th, the small town made the news for beating Canada’s all-time heat record. That week temperatures had been steadily climbing from the mid to high 40s and our little meteorological set-up in Ashcroft, perhaps an hour’s drive from Lytton, actually read 50°C on June 29th.

Photos left to right: The temperature reading taken on June 29th, 2021 & my home metereological unit. Whether the reading was accurate to a tenth of a degree, I don't know, but it certainly felt hotter than anything I could have imagined.

My relatives in Norway were calling, checking in on me, knowing I lived somewhere near Lytton. They were asking how the place was doing, how I was doing, and if it really was that hot.

I tried to tell them about how the wind felt like a hair dryer and blew through our dying, yellowed birch trees. Or how the crackling of dry grass and the sounds of the cicada’s high-pitched whir had replaced beloved birdsong. How the doorknobs on the inside of the house were too hot to touch. I told them how much I missed Norway’s cool summer nights.

I have described how my heat stroke left me feeling dull and damaged, but just as upsetting is thinking back to the fear and worry I felt leading up to my heat injury. I am haunted by the memory of trains screeching along the rail lines on either side of the Thompson River at 48°C. My stomach churns when I remember that on the same day that Lytton was razed by fire (fire that experts say was likely sparked by a CN train) the fire alarms were going off inside of our house. It was emergency sensory overload. Being just 80 km away from ‘Canada’s Hot Spot’, my experience feels eerily similar to what one Lyttonite described as perpetual oven door open temperatures. That is: simply too hot.

Underserved and overlooked

Although the residents of places like Lytton, Lillooet and Ashcroft are accustomed to severe heat, that doesn’t make our experience with climate-driven heat waves or wildfires any less severe. These are low-income rural communities living on unceded, unserved territories. They are towns with many Indigenous residents and elders, living on land that has been repeatedly parceled up by expansionist-Canada; its railways and forestry, mining and mills – and by its colonial land-reserve system that has left both literal and figurative scars across the lands.

These disproportionately affected towns dot a now-defunct gold-rush corridor. They are mostly lacking major emergency healthcare facilities, and are definitely not built to withstand an onslaught of climate-fueled disasters. A recent study from the Canadian Journal of Forest Research confirms just how devastating wildfires are for rural communities, and even more so for Indigenous people – as those living on First Nations reserves now make up nearly one third of all wildfire evacuees across Canada.

Leading up to the unprecedented heat forecast for the Heat Dome, people across BC were offered a totally inadequate, one-size-fits-all heat warning from the provincial government; 'Stay indoors with the AC on, stay hydrated, wear a hat. If you have to evacuate, go stay with friends or family...' The assumption that everyone has a social safety net, or friends with extra rooms and air conditioning was not only insulting, but totally irresponsible.

There were no location-specific public outreach recommendations, no health care mobilization plans, no heat injury information or patient follow-up. Rather, the formal approach to heat so hot it’ll make your mind melt was: ‘fend for yourself’.

Residents of the Thompson Nicola Regional District (TNRD) explained how precarious their situation was, but it still took the BC government 21 days after the Lytton fire to declare a state of emergency. That’s three weeks spent waiting for the government to recognize the severity of the situation for at-risk residents. That’s three weeks despite the BC Coroners Service’s early report on heat-related deaths from the Heat Dome, despite the rising number of fire evacuees struggling with the logistical challenges of finding temporary housing throughout the province. Despite wildfires tripling in size. Three weeks.

And, just like communities kicked into gear during last year’s flooding season with little to no help from the government, so too have they mobilized during this year’s heat waves and wildfire season. Local alert systems were put in place through a check-on-your-neighbours phone tree, other neighbourly supports were mobilized by the mostly-volunteer Ashcroft Hub. Along the Skeetchestn Reserve, in Spences Bridge and in Ashcroft, local volunteer firefighters and Indigenous controlled-burn experts fended off blazes, some using filled kiddy pools and buckets.

But even the most skilled community members dialing out updates through active Facebook groups (or the good luck of having an extremely hands-on, communicative mayor like Barbara Roden) can't make up for the gaps left by real planning measures. All of this is unsafe and unfair, and based on past experience, it's to be expected.

Who is in charge here?

Without government coordination for climate-related heat and emergency events, we all saw what happened. The Heat Dome took the lives of over 500 people, not counting deaths from wildfire smoke, and as of early August over half a million hectares have burnt by wildfires that have displaced thousands of people.

That’s not to mention the billions of dollars it will cost to rebuild, or the billions more it will cost to put adaptation measures in place. This province is woefully unprepared, and the provincial government’s Climate Emergency and Preparedness Plan looks like a vague consolation, when what our communities need are concrete plans.

Think of how many lives we could have saved had we been given the proper tools to care for ourselves and each other. Think of how many hundreds of thousands of hectares of grasslands and forests could have been saved if Indigenous fire management expertise hadn't been left out of fire-fighting efforts.

In the BC interior, the impacts that industry and climate change have on our communities are no longer abstract. But nothing could have prepared me for the heartbreak I felt on the night of June 30th, skies black with smoke watching as ash fell from the sky onto my skin from the Lytton fire.

Rural poverty and environmental racism have kept these towns and villages out-of-sight and out-of-mind for too long, and living here makes it easy to feel abandoned. Feeling invisible is made worse when visitors make their way through wrecked towns, stopping to take photos or to fill up hotel rooms, without offering to help. Many wildfire evacuees have to pack up multiple times as evacuation orders continue in the towns where they’ve sought refuge. Knowing that this may happen over and over during a single fire season makes the future seem like a terrifying place, full of re-lived trauma.

When the IPCC’s latest report confirms just how dire the situation will become next year, and the year after that, indefinitely – it’s easy to lose all hope. When you drive along the highway for hours alongside Trans Mountain pipeline (TMX) construction, it’s easy to become enraged. When the federal government has the audacity to treat us all like children with their oil-revenues-will-pay-for-climate-plans justification for building TMX, it’s easy to feel crazy.

Why do stories of climate pain (as seen around the world this past month) need to be put on display in order to spur real action? Why won’t governments treat their commitments to rural communities with the same urgency as they treat threats to industry? Threats to the market? Why are we still pumping money into the fossil fuel industry when they are the ones most responsible for this mess?

Surely there’s another way.

West Coast’s Climate Law in Our Hands program knows that planning for climate impacts and uncertainties must involve accountability from our governments and major polluters. We also look for different ways to include the public on important consultation processes around BC’s climate plans. You can join the conversation by signing up to receive updates, and if you have personally faced injuries from climate change, we’d love to hear from you as well.

For a list of all wildfires currently burning in the province, visit http://bit.ly/2HCKBod. For updated evacuation orders and alerts in the region, visit the TNRD dashboard at https://bit.ly/3dcIk0L.

Top photo credit: Julia Kidder (View of Lytton Complex Fire from Ashcroft, July 2021)