About one out of every four British Columbians relies on wells for drinking water. Groundwater is also essential to BC’s agricultural sector and is critical for habitat for salmon and other fish species. And British Columbians have been incensed that large companies can take our groundwater free of charge. And so it’s welcome news that BC is planning to finally regulate groundwater use under the proposed Water Sustainability Act (which the government is consulting British Columbians on until November 15th). But we need to be sure that these new rules on groundwater use don’t lock in unsustainable water use, and allow us to get a handle on how groundwater should be licensed is BC.

Here’s how the Water Sustainability Act (WSA) proposal would regulate groundwater:

Here’s how the Water Sustainability Act (WSA) proposal would regulate groundwater:

- All existing groundwater users – except domestic wells – would get water licences based on their historic use of water. There will be no consideration of whether that level of water use is sustainable or best serves the public interest, although the WSA would allow the government to consider water efficiency standards.

- Domestic well users will be encouraged to register their wells in the province’s wells database. Once registered, possible impacts on the well user will be considered in future requests for licences or amendments to licences. Domestic well users will not be allowed to receive a water licence unless an “area-based regulation” is passed requiring such licences.

- New non-domestic well users will be required to obtain a licence before using groundwater. Large-scale groundwater users (250m3/day or more) will be required to pay a nominal amount for their water, and (as with large-scale surface water) will be required to monitor and report their water usage.

So what does that mean for the health of groundwater aquifers and the environment, and for other water users?

What does a licence get you?

So what are the owners of existing wells getting when they get a licence?

Well owners currently have a right to pump water from the ground; however if other well users pump from the same fresh water source and cause the well to dry up or become saline, an owner has no recourse. The rights of groundwater users have been described by the BC Court of Appeal as similar to other “fragile” rights that can be extinguished by other users. Indeed, it is this unregulated access to water that has led to over use of aquifers in some areas of British Columbia.

As proposed, new groundwater licences will give well owners “priority” over anyone who starts pumping from the same water source at a later date. Licences will have a “priority date” based on when the well was first drilled and used. Legally a water licensee can insist that other users who have a more recent “priority date” stop taking water in times of scarcity. This is an attempt to bring unregulated groundwater use with the controversial “First In Time, First In Right” (FITFIR) system of water allocation.

Because of the “fragile” nature of groundwater rights, the proposed WSA had an opportunity to move away from the FITFIR model, and instead clarify that environmental flows, drinking water, agriculture or other publicly supported water uses had priority. However, the government has decided not to move in this direction.

So the proposed WSA would not simply “grandfather” existing wells by giving them licences, it would enhance and expand the rights of the well users – giving them the new right to claim priority over other, subsequent users.

Groundwater use and aquifer health

Obviously allowing unregulated access to groundwater can compromise aquifer health, as well as impact on the health of streams on the surface. So regulating groundwater is a positive, if long overdue, development.

But current use of BC’s wells is not always sustainable or environmentally appropriate. By accepting existing wells as a guaranteed basis for a water licence, the proposed Water Sustainability Act will be locking in unsustainable use of groundwater. It is essential, particularly for oversubscribed areas, to re-examine those licences to ensure that the water use is sustainable and maintains the health of the aquifer. In addition to overuse, climate change is likely to have an impact on groundwater supplies, particularly in the interior of BC.

The rights of different water users

If I held a surface water licence since (say) 1980 to use water for domestic purposes from a stream, and I’d been paying year after year to use that water, I’d feel a bit annoyed that a well owner who’s been taking free well water since 1970 from the aquifer that feeds my stream will now (under the Water Sustainability Act) get legal priority over my “junior” licence, and can stop me using surface water in times of scarcity.

But there’s even less clarity, and more potential for conflict, between domestic (unlicensed) well users and licensed well users. Because of how groundwater flows, the impact of one well on the water in nearby wells can be considerable, even if the well use is not affecting aquifer levels.

The WSA Proposal says that the interests of registered domestic well owners will be considered in applications for new water licences.

The WSA Proposal does not say that registered domestic wells will be considered when transitioning existing (non-domestic) wells to their groundwater licences. However, we are informed by Ministry of Environment staff that where the Ministry is aware of an existing localized conflict between well users, they will consider it in granting the transition licences, and that the date that the domestic well was first used (as recorded in the Wells Database) will be taken into account. In areas of wide-spread conflict, the impacts on domestic users will not be addressed in these transitional licences, and will instead need to wait for a Water Sustainability Plan.

After all the initial groundwater licences have been handed out, and (hopefully) most domestic wells are registered, there will still be conflicts – whether due to over-allocation, new licences that have unexpected impacts, climatic changes that decrease aquifer depth, etc. A well user with a water licence has an entitlement to the continued flow of water before other licensees with a lower priority date. Legally that right could be enforced either by the Ministry of Environment or in court.

But domestic well owners won’t have a licence – just a record in a database. So what, we asked, is a domestic well owner – who has registered – to do if his or her well runs dry? Does he or she need to take on the (expensive) job of drilling a deeper well? Or can he or she insist that other more recent well users stop using groundwater to restore the original aquifer levels?

Ministry of Environment staff emphasized that it was the responsibility of the well owner to make certain that their well had been drilled deep enough to deal with expected fluctuations in the aquifer level. In other words, if you’ve only drilled to a depth of 50 feet, but water levels in the aquifer regularly fluctuates from 40 feet to 60 feet, then you can’t complain if your well goes dry.

“Okay,” we said. “Let’s say the well owner did drill a deep enough well, and it still goes dry.”

Well then, we were told, “It depends.” Let's just say that answer makes us worry about how much protection domestic well owners will actually have.

First Nations and groundwater licences

It is well established in Canadian law that a First Nation has a right to be consulted on government decisions that may affect rights that they have established or which they are credibly asserting. It is also indisputable that in some, perhaps many, cases groundwater use can affect the legal rights of First Nations. In Halalt Nation v. BC the trial judge said (in reasons that were overturned on other grounds):

The evidence establishes that there is not an impermeable barrier between the Chemainus River and the Aquifer as the River flows through I.R.#2 adjacent to the site of the Project. The two are intricately connected. The groundwater feeds the Chemainus River and influences its flow levels. The River is, and has been traditionally, integral to the lives of Halalt because of its fish and fish habitat, plants and bathing holes. It sustains the animals the Halalt people hunt and the plants they gather. The Aquifer’s groundwater is a significant source of the water levels for the entire length of the Westholme side channel. The Aquifer is of central importance to the sustenance of fish and fish habitat. The groundwater warms the side channel in the winter and cools it in the summer. … I go no further than to say that Halalt has an arguable case for a proprietary interest in the groundwater of the Chemainus Aquifer, most of which underlies I.R.#2.

In my view the province faces a formidable problem in that the proposed legislation seems to purport to limit the government to considering only a narrow concept of "beneficial use" before convert existing wells into water licences. To the extent that the Crown, with this language, is attempting to to legislative itself out of its constitutional obligations, then this is highly inappropriate. Since the licences entrench the water uses, and represent government endorsement of those uses, the government cannot credibly claim that the change does not at least potentially affect First Nations’ rights.

This problem is exacerbated by (so far as we understand) a failure to consult First Nations in developing the legislation and the extension of the First In Time, First In Right system, which many First Nations organizations strongly opposed in the consultations that did occur, to groundwater.

Recommendations

Government should have the powers and responsibility to manage aquifers to maintain the health of the aquifer and associated surface water flows. This must include the ability, through licence reviews, to adjust water licences, including reducing the water allocation, as required based on new data, changes in the climate or other changing circumstances.

Current-well users should not receive final licences, or those licences should be fully reviewable, until:

- At least 5 years of water monitoring data for the aquifer obtained under the new monitoring requirements is available;

- The licenses can be assessed to ensure that the use of the aquifer does not exceed recharge rates and does not negatively impact the health of the aquifer or the health of nearby streams;

- Any constitutional obligations to consult First Nations regarding specific licences can be addressed.

If, at that time, current levels are not sustainable, licences must be adjusted (possibly through Water Sustainability Plans) to ensure that use rates are sustainable and do not negatively impact the health of nearby streams.

The rights of domestic well owners to the continued flow of water in their wells, as against licensed well owners, should be clarified.

By Andrew Gage, Staff Lawyer

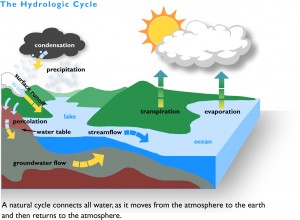

Hydrological Cycle graphic taken from Ministry of Environment Living Water Smart Blog.