A Guest Post by Bonnie Docherty, Lecturer on Law and Senior Clinical Instructor, Harvard Law School International Human Rights Clinic

The ongoing tension in British Columbia between mining interests and First Nations concerns has resurfaced yet again this fall. In September, Premier Christy Clark announced her B.C. jobs plan, in which she promised eight new mines and the expansion of nine existing mines by 2015. Although the plan pledges in general to “work more closely” with First Nations, it does not mention consulting with First Nations about those mines and in fact calls for expediting the granting of exploration permits, which many First Nations believe are currently issued too quickly. On November 7, the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency is scheduled to decide whether to review a proposal from Taseko Mines Ltd. for a New Prosperity Mine in Tsilhqot’in First Nation’s traditional territory. The same federal agency rejected an earlier version of the proposal in 2010, and this year, the Tsilhqot’in have renewed their vocal opposition to the mine, describing the new proposal as worse than the original one.

In the midst of these developments, the coalition First Nations Women Advocating Responsible Mining (FNWARM) brought stakeholders together in a panel entitled “The Future of Mining in British Columbia: Cooperation, Not Conflict.” The panel, co-sponsored by the University of Victoria Environmental Law Club, included high-level representatives of the mining industry and First Nations. The B.C. government declined the organizers’ invitation to participate, however, which demonstrated the challenges of achieving the full cooperation the panel aimed to foster.

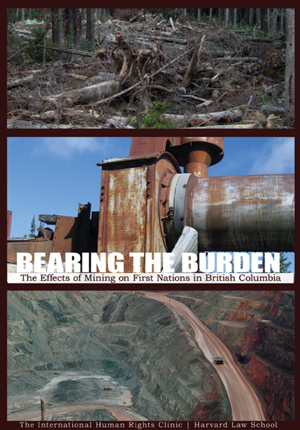

I joined the panel as co-author of the 165-page report Bearing the Burden: The Effects of Mining on First Nations in British Columbia, published by the Harvard Law School International Human Rights Clinic in 2010. My remarks, which I elaborate on below, analyzed the aboriginal rights to which First Nations are entitled, illustrated the undue burden of mining First Nations bear despite those rights, and offered recommendations for how stakeholders could better share the burdens and benefits of this industry. I sought to bring an aboriginal rights perspective to the tensions between First Nations and mining in British Columbia, most recently exemplified by the jobs plan and Prosperity Mine proposal. Viewing the situation through a rights-based lens can help illuminate the problems and provide guidance for how to address them.

Aboriginal Rights Law

International and Canadian law both grant indigenous peoples special protections that are applicable to situations involving mining. At the international level, these protections stem from rights articulated in treaties to which Canada is party and is thus legally bound. The treaties include the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. The rights also appear in the UN Declaration on the Right of Indigenous Peoples, a non-binding but widely accepted set of standards that Canada endorsed in November 2010.

According to these legal instruments, First Nations have the right to participate in decision-making about the future of their lands and resources. In addition, First Nations have the right enjoy their cultures. Because their cultures are inextricably linked with the environment, this right requires that First Nations be able to use their lands. Finally, First Nations have the right to dispose of their natural resources. As party to the treaties mentioned above, Canada is legally obligated not only to respect these rights itself but also protect First Nations from abuses by third parties, such as mining companies. A critical first step to meeting these obligations is to ensure heightened scrutiny of mining activities that threaten First Nations’ territories.

Canadian law also establishes special protections for First Nations. An extensive and complex body of jurisprudence interprets the aboriginal rights laid out in the Canadian Constitution Act of 1982. This case law permits infringements, such as mining, on First Nations’ territories, but it makes the infringements subject to safeguards that have increasingly protected First Nations’ interests. The 2004 Supreme Court case Haida Nation v. British Columbia is particularly significant on this front. It mandates that the government consult with and accommodate First Nations communities that might be adversely affected by proposed activities on their traditional territories. The case requires “good faith efforts to understand each other’s concerns and move to address them.” Together, therefore, international and Canadian law call for heightened scrutiny of proposed activities, such as mining, that threaten the rights of aboriginal peoples.

An Unfair Burden

Despite their legal rights, First Nations have borne an unfair share of the burden of mining in British Columbia. This burden has existed at every stage of the mining process—from claim registration to exploration to production to cleanup of abandoned sites. B.C. mining law offers some protections for First Nations communities, but it generally favors industry. On paper and in practice, the legal regime has failed First Nations in three major ways. It has provided inadequately for consultation. It has resulted in harms to the environment, human health, and First Nations’ cultures. Finally, it has produced limited benefits for First Nations communities.

Inadequate Consultation

First, the B.C. government has fallen short in its duty to ensure adequate consultation with First Nations about proposed mining projects. The problem is evident from the very beginning of the mining process. Under British Columbia’s Mineral Titles Online system, an individual needs only an easily obtainable free miner certificate, an internet connection, and a credit card to register a claim to a piece of a First Nation’s traditional territory. The law does not require prior notification of the affected First Nation, even though at this stage miners start to become invested in developing a site because they can do some preliminary exploration. At the next stage of full exploration, the B.C. Mines Act requires a proponent to submit a Notice of Work to First Nations before the proponent can receive a permit for activities on traditional territories. The First Nations, however, generally have only thirty days to respond. They have neither the time nor the resources to prepare a proper evaluation of a proposal in that window, yet Premier Clark has pledged in her jobs plan to expedite this process. First Nations have also had inadequate opportunities for consultation at the later stages of the mining process. The flawed consultation process has interfered with First Nations’ right to participate in decision-making about what happens to their land.

Harms to the Environment, Human Health, and Cultures

Second, the widespread mining activities in British Columbia have cumulatively and adversely affected the environment, health, and cultures of First Nations communities. For example, some First Nations have observed a decline in wildlife in their traditional territories. Noise, deforestation, and road construction have driven some animals away, and First Nations fear that those who remain may be contaminated by pollution from mining operations. Wildlife has traditionally been an important source of food for First Nations, and the unavailability of game has compelled some community members to change their diets, which has had negative health impacts. The recent challenges of hunting have also interfered with First Nations’ long-standing cultural practices. Due to these harms, First Nations cannot fully enjoy their culture, which is inextricably linked to the environment.

Lack of Benefits

Third, while bearing an unfair burden from mining, First Nations in British Columbia have generally received a smaller share of the benefits than other stakeholders. Some First Nations have reached revenue and profit sharing agreements with government or industry and had job training and employment opportunities. Research suggests, however, that these benefits have not been universal and that, in many cases, First Nations have found the benefits do not outweigh the harms they are experiencing. In other words, they have had limited say in and not accrued sufficient benefits from the disposal of their natural resources.

Recommendations

The adverse effects of mining stem from the failure to uphold the special protections guaranteed to First Nations by international and Canadian aboriginal rights law. These effects must be dealt with so that the undue burden is shifted off First Nations. Keeping full achievement of First Nations’ rights as the end goal can help guide the process of making that shift.

Most important, the B.C. government needs to reform its mining laws. An amended regime should ensure greater First Nations involvement in decision-making. For example, meaningful consultation should begin at claim registration, and the law should grant First Nations more time and more resources to respond properly to project proposals at any phase. Reforms should also increase protections for the environment, human health, and cultures, which would allow First Nations to enjoy the use their land. The law could lessen mining’s footprint by requiring more detailed baseline and cumulative impact studies as well as more rigorous monitoring. Finally, modifications to the law should expand the government’s existing revenue sharing program while encouraging mining companies to adopt comparable ones. Such programs would give First Nations more benefits from the disposal of their natural resources. As a whole, legal reforms would not only better safeguard First Nations’ rights but also provide increased clarity that would to be to everyone’s advantage.

Other stakeholders should join the B.C. government in playing a role in reducing the tensions between mining and First Nations. Mining companies should take more voluntary steps to improve relations with First Nations. While some companies have made efforts to work with First Nations, they should augment communication with the communities at all stages of the mining process, ensure fairness in benefit-sharing agreements, and provide increased training and employment opportunities for local First Nations. First Nations themselves should also take action, most notably by making their preferences explicit. In particular, they could facilitate a more just process if they clarified how they prefer to be consulted, what areas of land they believe should remain off limits to mining, and what types of economic benefits they value most.

The recent panel at the University of Victoria wisely called for “cooperation, not conflict.” The new B.C. jobs plan, the proposed Prosperity Mine, and the B.C. government’s refusal to participate in the panel have highlighted the challenges behind cooperation. Nevertheless if government, industry, and First Nations work together, they can achieve a system that both protects First Nations’ aboriginal rights and spreads the burdens and benefits of mining across all of the parties involved.

By Bonnie Docherty, Lecturer on Law and Senior Clinical Instructor, Harvard Law School International Human Rights Clinic

West Coast Environmental Law would like to thank Docherty for agreeing to prepare a guest post based upon her comments at the "Future of Mining in British Columbia: Cooperation not Conflict" panel on October 6th in Victoria, BC.