People have strong attachments to killer whales in British Columbia. They star in stories, art and legends of many First Nations and coastal communities.

Killer whales have matrilineal societies, with a mother or grandmother at the centre of the family, and lifelong close bonds between mothers and their offspring. Southern resident killer whales have a unique culture from other killer whale populations, using distinct vocalizations to communicate, find mates, and locate preferred prey.

The federal government needs to hear from you about how to protect the remaining 75 southern residents. You can comment on the proposed 2019 measures to address key threats to southern resident killer whales by filling out the federal government’s online survey. The deadline to comment is Friday, May 3, 2019.

Legal status and current prognosis for the southern resident killer whales

In 2003, southern resident killer whales (SRKWs) were listed as Endangered, the most serious “at risk” status under the Species at Risk Act (SARA). Last year federal Fisheries and Environment Ministers determined that the SRKWs faced an ‘imminent threat’ to their survival.

Extinction will occur without elimination or mitigation of the top three threats the SRKWs face:

- Prey availability (availability = abundance and the accessibility of chinook, coho, chum salmon),

- Physical and acoustic disturbance from vessels, and

- Contaminants.

The online consultation portal lists the federal government’s actions to date. But all too often, the government has acted only when a court forced them to act. Over the past decade, Ecojustice has launched numerous lawsuits to protect the SRKWs on behalf of the World Wildlife Fund Canada, David Suzuki Foundation, Georgia Strait Alliance, Natural Resources Defense Council, and Raincoast Conservation Foundation. West Coast supports these groups’ calls for SRKW protection.

Legally binding measures to save the SRKWs

The government proposes fishery closures to address prey availability; small vessel approach limits, speed limits and restricted areas; large vessel speed limits; and additional regulation of chemical contaminants. Here are our recommendations in response to these proposals:

1. Apply protective measures to the SRKWs’ entire legally designated critical habitat through legally enforceable measures.

There are two main concerns with the government’s proposed measures: They create an overly complex system of protection, and many of the measures are voluntary rather than regulatory, making them unenforceable.

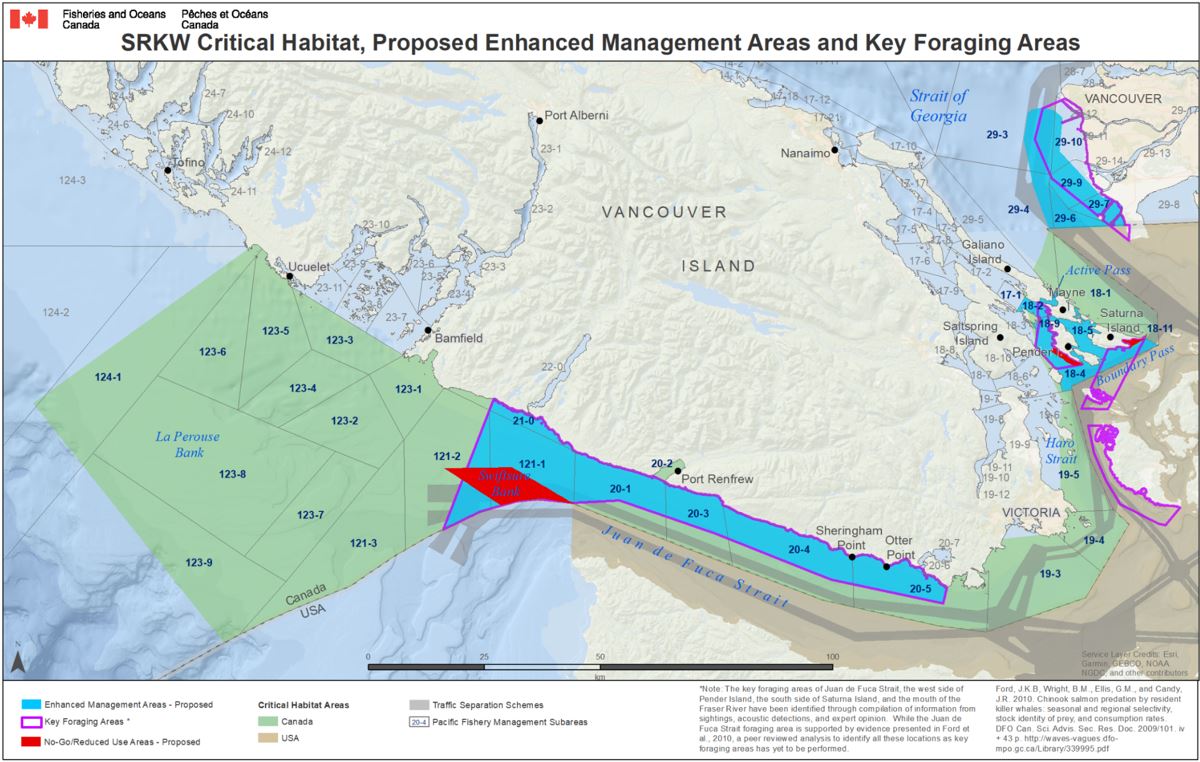

First, instead of using comprehensive regulations that apply to all of the SRKWs legally-protected critical habitat within the Salish Sea, the government has proposed carving up this critical habitat into smaller zones with different names: “enhanced management areas,” “sanctuaries,” “no-go” or “reduced use zones,” all saddled with an unclear regulatory basis.

This map shows the conglomeration of proposed zones and restrictions.

Designated critical habitat under SARA should receive the highest level of protection. Mandatory measures that apply throughout all the SRKW’s critical habitat are essential.

Protections should consider the impacts of increasing development and vessel traffic within designated SRKW critical habitat. The National Energy Board’s (NEB) recent reconsideration report on the Trans Mountain pipeline and tanker project found that it would likely cause “significant adverse environmental effects” on the SRKW, and the Indigenous cultural use associated with them (read more about the NEB’s report from our Staff Lawyer Eugene Kung).

A project imposing significant adverse effects to an endangered species within their legally-designated critical habitat should not be approved. Instead, we support recommendations such as setting underwater noise reduction targets for 2019 within key SRKW foraging areas.

Second, using voluntary approaches to protect the whales hasn’t worked. Mandatory regulations are preferable in the case of probable species extinction. As the Federal Court of Canada said in a SRKW case from a decade ago:

“The whole point of SARA is to provide protection for the critical habitat of species at risk in such a way that those protections cannot be set aside or modified through the exercise of ministerial discretion at some time in the future.”

Critical habitat is just that – habitat that is critical to the survival of the southern resident killer whales. Regulations should protect all critical habitat.

2. Make no-go zones truly no-go, or use a different name.

The government proposes small areas on the map as “no-go” or “reduced use” zones, or “sanctuaries”. More clarity is needed. The government intends to include a list of exemptions from this supposed “no-go” area, including exempting “vessels in transit,” so the term “no-go” is misleading. Similarly, the term “sanctuary” has no legal meaning under SARA.

True no-go zones are a good option for SRKW protection to reduce vessel disturbance in areas frequently used by killer whales for feeding. One example is Robson Bight (Michael Bigg) Ecological Reserve, a provincial marine protected area (MPA) created specifically to protect the rubbing beaches for the northern resident killer whales. Currently, restrictions on boating are voluntary in that MPA. We support regulating vessel traffic by creating enforceable no-go zones in key foraging areas for the SRKW such as around North Pender and Saturna Islands, as indicated on the map and in the online consultation.

3. Make the 400-metre approach distance applicable to all killer whales in all of the SRKW designated critical habitat.

Last year, the Marine Mammal Regulations were updated after a decade of regulation development and delay. The regulations imposed a minimum approach distance of 200 metres to killer whales in British Columbia. The restriction is primarily aimed at whale-watching boats.

Already it appears this approach distance is inadequate. Washington State passed new laws this month requiring a 400-yard minimum approach distance for following moving killer whales, and a 300-yard minimum distance for stationary whale watching. In the current proposal, the Canadian government proposes an approach distance of 400 metres within Fishery Closure Areas and Enhanced Management Areas.

We echo the recommendation from other environmental groups who are commenting on this proposal: make the 400-metre (or greater) approach distance applicable to all small vessels, including fishing vessels, and make it applicable throughout the southern resident killer whale’s critical habitat.

A 400-metre minimum approach distance has been used to protect endangered beluga whales and regulate whale watching in the St. Lawrence River and Saguenay estuary in Quebec since 2002. A similar uniform restriction should apply in BC waters, including an update to current regulations as has been done in Washington state.

4. Make the voluntary ship slow-down mandatory, and applicable to sightings of all killer whales.

The current proposal is for a voluntary 1000-metre “go-slow” buffer (requiring vessels to travel at 7 knots or less) in proximity to southern resident killer whales, but only within “Enhanced Management Areas” as shown on the map.

These speed-reductions should be mandatory throughout all SRKW critical habitat, and should apply to all small vessels and to all killer whales. Identifying southern resident killer whales from other types, such as transient killer whales or northern residents, requires experience and knowledge that shouldn’t be expected of all boaters.

5. Fishery closures

The recently announced reductions to Chinook salmon harvest are an important measure to restore at-risk salmon populations and key prey for the southern resident killer whales. We echo recommendations from other groups that these must be implemented with sufficient monitoring and enforcement to ensure that pressures on Chinook populations are sufficiently reduced.

Improving access to prey must also involve removal of competition in the identified key foraging habitat. We also support recommendations to close these DFO-identified key foraging habitats to all salmon fishing vessels from May 1st to September 30th, the time when southern resident killer whales are generally present in the Salish Sea in the highest numbers.

6. Harmonize shipping controls on large vessels in SRKW critical habitat with the US

The United States maintains an International Maritime Organization (IMO) sanctioned Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS) in the Strait of Juan de Fuca and its approaches, in Puget Sound and its approaches, and in Haro Strait, Boundary Pass, and the Strait of Georgia. These schemes are used to regulate the marine traffic in busy or confined waterways.

Canada does not currently propose to develop a complementary TSS in Canadian waters. We encourage the government to investigate this option, as Canada has the option to seek IMO approval for a TSS in its waters to complement the existing US initiatives.

7. Accelerate regulation of toxic contaminants

We fully support the government’s efforts to further restrict toxic substances. We look forward to the completion of the commitment to amend the Prohibition of Certain Toxic Substances Regulations, 2012 to further restrict five chemicals (flame retardants, oil and water repellent) and prohibit two additional flame retardants if they are confirmed as toxic.

Bold new move – legal rights for whales

Another legal option is to give the southern resident killer whales legal rights, which would amplify their voice in courts and legislatures. Extending these rights to the whales could be the key needed for their survival. Many groups are calling for the introduction of this bold move: the Legal Rights for the Salish Sea project, the Earth Law Center, the Lummi Nation, and more.

Make your voice heard: Tell the government that “strong laws save whales.”

Send in your feedback today.

Photo Credit: Miles Ritter