Alright Vancouver Island peeps. Listen up:

If you live on Southern Vancouver Island, or in Nanaimo or around Fort Rupert [where my people the Kwakiutl and Komoyue call home], and whether you are Indigenous or not, you are bound by a treaty – a solemn promise made between James Douglas . . . representing the Crown, and one of 14 First Nations.

These words were repeated throughout the weekend at a conference I attended recently, called “First Nations, Land, and James Douglas: Indigenous and Treaty Rights in the Colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, 1849-1864.”

The conference brought together historians and legal scholars, as well as Indigenous people who are direct descendants of the signatories to the Vancouver Island Treaties (aka Douglas Treaties). Together we had rich conversations about our profoundly different views of land and resources, as well as what it means to live under these treaties today. Because these are pre-confederation treaties, they are foundational to Canada’s constitution and protected under s. 35, but it’s unclear exactly what that means on the ground.

The conference began Friday night with opening words from the keynote speaker, Saanich Elder STOLȻEŁ John Elliott Sr., who grounded us with stories. He shared an Indigenous cosmological perspective and we were reminded of the connectedness to sacred places. This connectedness is illustrated through teachings about non-human beings such as the wind beings.

John told us the light used to be a human being, and his wife was the morning star. He told us about pebbles that grew into mountains and about how even today, some people will take one of those black stones as a prayer stone and as a reminder of the relationship to islands who are relatives – sisters – who grew from those stones that had been tossed into the ocean.

And he shared a beautiful teaching about cedar. To many people around the world, cedar is considered sacred. In my Kwakwaka’wakw community, cedar is considered the Tree of Life and its image is used on regalia such as button blankets. Other people use cedar for medicine or prayers. John told us cedar trees were made from the kindest people and that cedar serves as a reminder of the responsibility we have to be kind to one another.

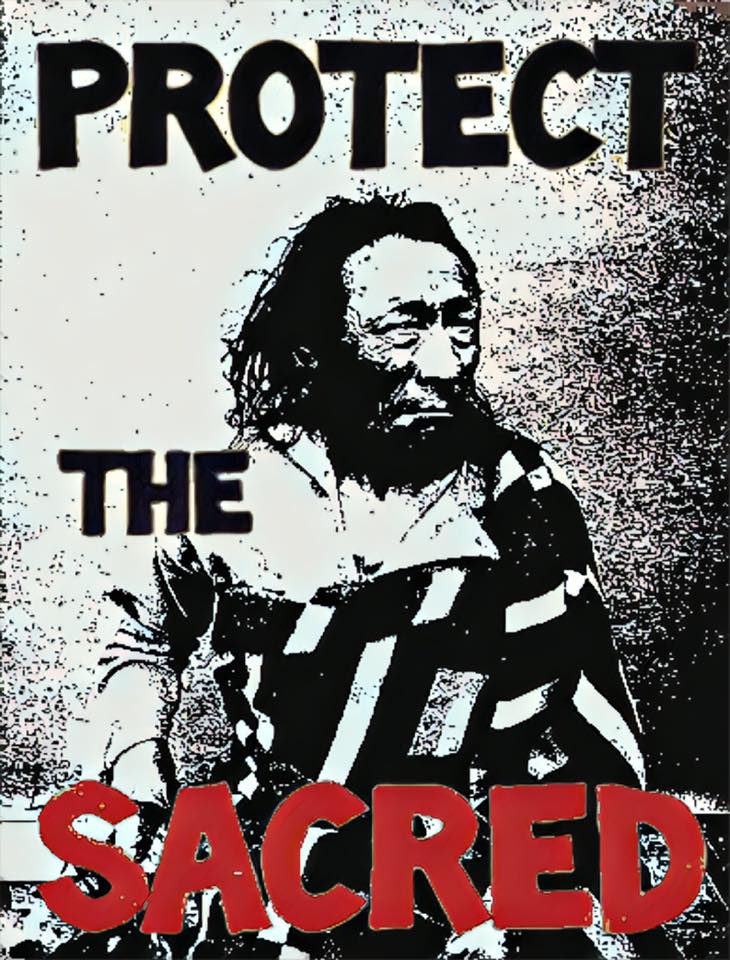

The next morning, John again reminded us of the sacred trust the Creator gave the WSANEC people to look after the land. “Natural resources are relatives;” he said. The wind, the life in the salt water, animals, birds – all are deserving of respect, and from a WSANEC perspective we have obligations to look after them.

Through the work of John Elliot and XEMŦOLTW̱ Dr. Nick Claxton, we know the law of this land is based upon the values and beliefs included in these WSANEC perspectives, and that laws and beliefs are inseparable. Nick reminded us that Indigenous languages such as SENĆOŦEN are the voice of the land. Songs, prayers and place names also help us understand that relationship between humans and land.

These understandings of home and connections to the lands and waters, along with the creation stories that tell how the WSANEC people got here, create the context and backdrop to the Douglas Treaties. This cosmology and worldview, and the loving relationship with land, brings responsibilities. And importantly, these perspectives come from a time long before any treaties were signed. So from their perspective, the starting place for treaty interpretation is with the concept that land is a sacred gift from the Creator and therefore could never be surrendered.

I was never taught this in law school. At least not this way.

Our ancestors who signed these treaties were reasonable and reasoning people. Through stories like the ones we've been analyzing through the RELAW Project, we know that they cared deeply about – and were connected to – the environment around them. WSANEC (and other Indigenous perspectives) can benefit everyone living in treaty territory by reminding us about what it means to have a loving relationship and responsibility to the lands and waters around us.

I love what Ojibway artist and environmentalist Manzinapkinegego’anaabe / Bombgiizhik Isaac Murdoch says about treaties:

When they signed those treaties, our Nations did not sign up for an Environmental Catastrophe. Let's unite and organize a full on massive resistance against fossil fuels. We have nothing to lose and everything to gain. ❤ #WaterIsLife #Powertothebabies

The planet needs what Indigenous perspectives have to offer – and we all need to listen deeply.

HA’em!