As the project lead for the RELAW Project (Revitalizing Indigenous Law for Land, Air and Water), I often reflect upon the importance of our work – especially this summer, as I was feeling the effects of the wildfires in BC, hearing about the floods in Asia and the destruction from hurricanes Harvey and Irma.

It seems every day lately there has been some kind of horrific climate-related news. All of it reminds me about the importance of the work we’re doing, and that the planet needs the kinds of messages and results offered through the RELAW project.

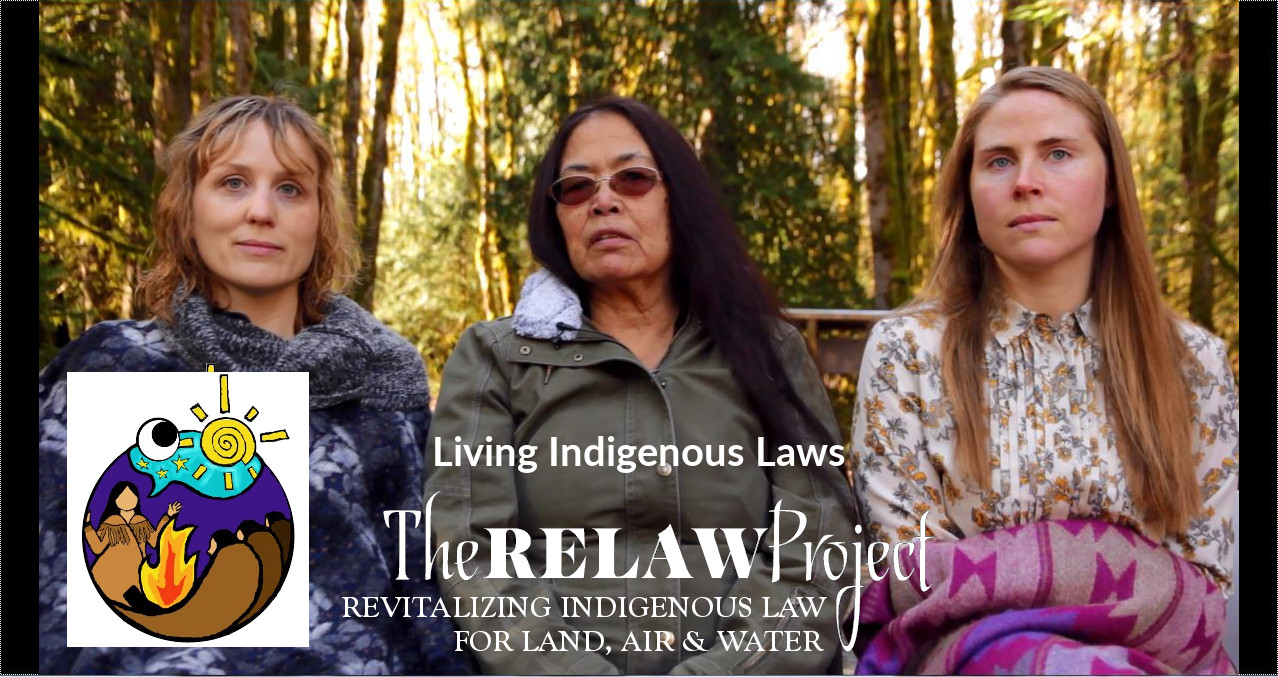

To demonstrate what this work is all about, today we’re launching a new short film called RELAW: Living Indigenous Laws.

Through the RELAW project, we’ve been working with Indigenous nations who are revitalizing their Indigenous laws and applying them to the environmental challenges they are facing today. In this work, we are reminded how Indigenous legal orders generally respect animals and the natural world, and encourage humans to act on our responsibilities.

The values embedded in Indigenous legal orders have relevance and are needed in today's world, and sometimes we worry we can't do this important work fast enough.

Although I'm terrified by what I hear about recent climate-related events in the news, I'm learning not to turn away. I'm doing my best to face this terror and instead trying to find useful ways to respond with my family, community and work. I’m learning about things like food and water security, alternative forms of transportation, living without fossil fuels and plastics, building community, understanding “intersections,” and seeing – as my Kwakiutl grandfather would have said – how everything is connected: “We one. We all one.”

It all began to hit home one morning this summer when I was sitting on a crowded Vancouver bus. I'd walked the two short blocks through our smoky neighbourhood down to the bus stop, and despite the short walk, the smoke made my whole body tired.

When I blinked, I felt a fuzziness in my eyes and wondered if this was because of the ash and particulate matter in the air. With every blink, I was reminded of the realities of climate change and the ways humans have been treating the planet as a means of getting rich – taking, taking, taking, without regard for the consequences.

My mind drifted, and I began thinking of my connection to this place, here in Tsleil-Waututh territory where I grew up. As the bus crawled along the bridge over Burrard Inlet, I recalled a story from an elder I'd met decades ago. Mucksin described paddling a canoe from her Capilano home to what is now Stanley Park, where her grandmother, Ta’ah, had a cabin and together they dug clams on the beach most of us know as Lumberman's Arch.

I was on a bus right above this same beautiful body of water, Burrard Inlet, where as children we swam and where Mucksin had paddled and dug clams. The Tsleil-Waututh people have stewarded these lands and waters for many generations, guided by Indigenous laws that demand respect for the natural world – laws that are still alive and well today.

But now there was a stench coming in the open bus window, bringing me back to the summer of 2017 and the terror of this time.

Everyone is hurting: people, animals, fish, trees. In the news, we see stories of wild horses burned alive in Tsilhqot’in Nation territory, exhausted moose trying to escape the fires, the velvet on their antlers singed. In response, the Tsilhqot'in have called on the BC government to suspend the fall moose hunting season. I’m reminded of the leadership of the Coastal First Nations who banned grizzly bear trophy hunting under their own laws long before the Province got around to introducing the same ban.

Now, as we enter the second year of the RELAW Project with a new cohort of Indigenous partners, I am reminded once again about the importance of our work.

What would the planet look like if we all, along with government and industry, took Indigenous legal orders seriously? Or, as Gitga’at RELAW researcher La’goot says, if we were to acknowledge our connection to the plants, animals, and spiritual beings we don’t see on a daily basis? Our hope for RELAW is that the project helps to bring back those connections.

I encourage you to watch the film and think about the lessons we can all learn from living Indigenous laws and legal traditions.

In the words of my grandfather: We one. We all one.