In preparing a presentation about the collapse of the enforcement of environmental laws in British Columbia over the past decade, I noticed something interesting: violators of the Wildlife Act – primarily hunters and fishers - are almost 4 times as likely to be convicted as violators of the Environmental Management Act – who are primarily commercial and industrial operations.

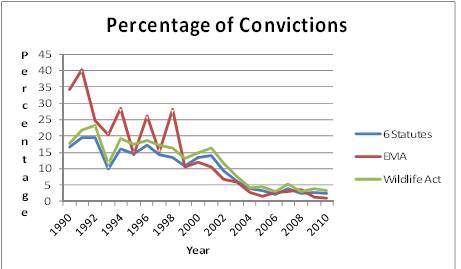

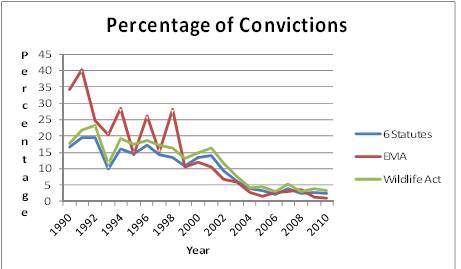

I’ve written previously that the Province is charging fewer and fewer environmental offenders, relying instead on tickets. By way of context, in the early 1990s about 16% of enforcement actions under 6 major environmental statutes* involved a conviction (the remaining 84% were given tickets). In the year 2010 (the most recent year for which figures are available), 2.5% of offenders were convicted of an offence. The graph to the right shows the decline in the percentage of offenders who are convicted. The blue line indicates the average for 6 environmental statutes, while the red and green lines show the Environmental Management Act (and its predecessor) and the Wildlife Act, respectively (more on them in a moment).

I’ve written previously that the Province is charging fewer and fewer environmental offenders, relying instead on tickets. By way of context, in the early 1990s about 16% of enforcement actions under 6 major environmental statutes* involved a conviction (the remaining 84% were given tickets). In the year 2010 (the most recent year for which figures are available), 2.5% of offenders were convicted of an offence. The graph to the right shows the decline in the percentage of offenders who are convicted. The blue line indicates the average for 6 environmental statutes, while the red and green lines show the Environmental Management Act (and its predecessor) and the Wildlife Act, respectively (more on them in a moment).

As we’ve explained previously, tickets are generally for fines in the $200-$600 range. Convictions – where an offender is formally charged and is found by a court to have violated the law - are the big penalties that actually hold major offenders to account and create a real deterrence. See the table below for a comparison of ticket and conviction penalties for a select handful of offences.

As we’ve explained previously, tickets are generally for fines in the $200-$600 range. Convictions – where an offender is formally charged and is found by a court to have violated the law - are the big penalties that actually hold major offenders to account and create a real deterrence. See the table below for a comparison of ticket and conviction penalties for a select handful of offences.

But further questions emerge if we focus in on individual statutes.

Environmental Management Act

The Environmental Management Act relates to the discharge of pollution into the environment, mostly by industrial or commercial operations. This is the main piece of provincial legislation aimed at regulating industrial pollution emissions. Tickets for most offences under this statute run at $575, while convictions could be up to $1 million or 6 months in prison.

In the first 5 years of the 1990s, 30% of offenders under the Environmental Management Act received a conviction instead of a ticket (peaking at about 40% in 1991). This is well above the average for the ticket to conviction ratio during this time period, but that makes sense, since a $575 ticket for an industrial operator is hardly a deterrent.

But in 2010 about 1% of Environmental Management Act offenders were punished through a conviction.

Wildlife Act

Meanwhile, hunters, fishers and guide outfitters under the Wildlife Act were also receiving far fewer convictions in 2010 relative to tickets than they did in the 1990s, but not as dramatic a decline as offenders under the Environmental Management Act. In the early 1990s about 18% of Wildlife Act enforcement actions involved a conviction. In 2010 that figure had dropped to about 4%.

That’s still a major drop in convictions relative to tickets, but it means that in 2010 violators of the Wildlife Act were almost 4 times more likely to face a conviction under the Wildlife Act, than polluters, hazardous waste handlers and industrial operations who violated the EMA.

Let the punishment fit the crime

Ask yourself: Would a ticket for $345 convince someone who is hunting out of season under the Wildlife Act not to reoffend? It seems to me that the answer is quite possibly. I don’t wish to imply that 4% is an appropriate conviction rate for Wildlife Offences, and the Wildlife Act regulates guide outfitters, trappers, as well as those less legally employed in taking wildlife, and others who do make significant money from hunting BC’s wildlife for sport. But for a significant number of the people caught violating the Wildlife Act, it’s at least arguable that a ticket is an appropriate punishment.

Now ask yourself: Would a ticket for $575 convince someone who is disposing of industrial toxic waste in contravention of the Environmental Management Act not to reoffend? The Environmental Management Act offenders are much more likely to be businesses that make a significant amount of money from operations that cause pollution. As such, it’s much, much harder to argue that a $575 ticket is sufficient.

So what’s going on?

We’ve speculated before about reasons for the decline in provincial environmental enforcement. But what’s the reason for giving major polluters even more of a break than hunters and fishers?

Here’s some possible answers:

- It could be the ongoing impact of a 2004 directive that specifically instructed the Conservation Officer Service to be more “business oriented” in relation to commercial and industrial “clients”. I actually believe that those days are past, but it’s hard not to draw inferences from the fact that COS staff were at one time told to view Environmental Management Act violators as “clients”.

- Conservation Officers have the training and expertise to determine when a Wildlife Act violation has occurred. Determining whether a permit or code under the Environmental Management Act has occurred requires scientific and technical knowledge and/or testing – and cuts to the Ministry of Environment has reduced the staff with that knowledge and the budget to do testing.

- Large companies charged under the Environmental Management Act are likely to vigorously fight charges, while guide outfitters, trappers and hunters charged under the Wildlife Act with fewer resources are less likely to fight the charges. The prospect of lengthy battles may deter Conservation Officers from laying charges in the first place, and may also mean that fewer of the charges laid against large polluters end up as convictions.

- Cuts to the Ministry of the Attorney General may have reduced the ability of the government to carry on the more complicated Environmental Management Act prosecutions.

Clearly both the decline in enforcement generally, and the free-ride of some of the province’s largest polluters, is unacceptable. At the end of the day, the government needs to hire staff with the scientific and legal knowledge necessary to hold polluters, and other environmental law violators, accountable.

* - The above analysis of BC enforcement statistics focuses on 6 major environmental statutes: the Environmental Management Act (and its predecessor), the (Canadian) Fisheries Act, the Integrated Pest Management Act (and its predecessor), the Migratory Birds Convention Act, the Water Act and the Wildlife Act.