Zero charges, one recent conviction, two overdue reports – the numbers tell the story on fish habitat protection law enforcement in Canada

Two recent events have underscored the need for strong habitat protection in the federal Fisheries Act, which is why recent amendments to strengthen the Act are such welcome news:

- First, the organizers of a motocross race through fish habitat were sentenced to pay $70,000 for causing death to fish in what appears to be the only conviction under the Fisheries Act habitat provisions to occur in six years. The prosecution chose to run the case on the ‘death to fish’ part of the current “serious harm to fish” prohibition rather than the nebulous ‘destruction of fish habitat’ part of the prohibition (further set out below).

- Second, the statistics from two extremely overdue Annual Reports to Parliament from Fisheries and Oceans Canada show that prosecutors are not using the current weak habitat protection provisions of the current Fisheries Act.

As we have been saying for years, there is an urgent need to restore – and enforce – the “lost protection” for fish habitat in the Fisheries Act.

Lost legal protections

Prior to 2012, the Fisheries Act made it illegal (unless authorized) to cause Harmful Alteration, Disturbance, or Destruction (HADD) of fish habitat. The HADD prohibition was a bulwark of our environmental law safety net: see the partial listing of reported cases in Habitat 2.0 (see pg. 6 for how the HADD prohibition used to work.)

In 2012, the then government replaced the prohibition against HADD with a prohibition against causing "serious harm to fish," which was defined as "the death of fish or any permanent alteration to, or destruction of, fish habitat." It may just seem like a few edited words, but without explicitly prohibiting disturbance or non-permanent damage to habitat, the law permitted a much wider range of activities with potential impacts on fish.

Scientists and lawyers agreed that the 2012 amendments resulted in a law that was both scientifically suspect and legally toothless. At the time, the government justified the changes by saying that the HADD provisions were too strict – going beyond what was required to protect fish habitat.

However, an illuminating article by professors Martin Olszynski and Brett Favaro challenged that claim by crunching numbers on habitat loss under the HADD provisions. They found that even before the Fisheries Act was weakened in 2012, fish habitat loss was occurring on a worryingly massive scale: a net loss of over 2 million square metres of fish habitat over a six month period in 2012 alone. It’s anyone’s guess how much habitat was lost after the weaker version of the law came into effect.

We can only speculate that the lack of clarity about what “serious harm to fish” means was a reason why prosecutors gave up on enforcing the Fisheries Act in relation to fish habitat damage in recent years. Now, the new numbers and information prove that regulators and prosecutors have virtually abandoned the use of this legal provision, as there have been zero prosecutions for fish habitat damage in recent years.

Extreme facts needed for conviction under 2012 Act’s weaker provision

The only apparent reported conviction over the past six years shows the level of effort required to obtain a conviction under the 2012 rules. Two defendants were sentenced last week in Alberta for causing the "death of fish" in violation of the Fisheries Act. The motocross race that gave rise to the charges occurred in 2014, and trial and conviction occurred in 2018.

In R. v. French, the Alberta Provincial Court imposed $70,000 fines on motocross club race organizers who had ignored regulators’ warnings about the need to build temporary bridges over multiple creeks in the race site due to the potential for damage from the vehicles to the creeks’ fish habitat. In addition to providing fish habitat, the fish in the creeks (the West Slope Cutthroat Trout and the Bull Trout) are listed as threatened species under the Species at Risk Act.

Videos introduced at trial from cameras installed at the race site showed the motocross bikes crossing through the creeks directly over the cobbles used by young trout, crushing them. The racers left large plumes of sediment in their wake, potentially affecting both eggs and young trout by reducing water flow through the gravel and cutting off oxygen to fish and embryos.

The judge found beyond a reasonable doubt that both Bull Trout and West Slope Cutthroat Trout died as a result of this race. The convictions were possible due to the extensive video and photographic evidence, expert evidence, evidence of previous warnings, and months of investigation. The detailed evidence underscores how much work is required under the vague 2012 habitat provision to achieve a conviction.

According to the judgment, the Crown’s position was that the motocross racers caused the death of fish. The Crown did not argue that the racers caused "permanent alteration or destruction of fish habitat." Although it’s impossible to say with certainty why the Crown decided not to proceed with the habitat-related provisions of the prohibition, this decision supports our observation above that the language of the “serious harm to fish” provision is too uncertain, and that prosecutors feared that this uncertainty jeopardized the probability of obtaining convictions. In the end result, the judge found that the race was a factual cause of the death of fish.

While prosecutions are time consuming, expensive, and involve a high burden of proof, they are an essential part of the regulatory toolbox. A lack of prosecutions is evidence of a lack of care for safeguarding fish habitat.

Public land, public water – public information?

Monitoring enforcement of this key legal provision is challenging. Negotiated settlements are unreported, and many provincial court decisions are omitted from legal databases. While environmental prosecutors share these decisions among themselves, the public has to search for cases and data on fish habitat and pollution charges and convictions by tracking news releases, filing access to information requests, or both.

One other tool to assess enforcement is the Annual Report on the administration and enforcement of the fisheries protection and pollution prevention sections of the Fisheries Act, which Fisheries and Oceans Canada is required, pursuant to section 42.1 of the Act, to table before Parliament “as soon as feasible after the end of each fiscal year” (being March 31st of each year). But recent practice shows a worrying trend of delay for these reports.

The government quietly released two extremely overdue reports for both 2015-16 and 2016-17 just last month. The reporting period for the first overdue report ended March 31, 2016 (over three years ago), while the second report is late by more than two years. The statistics are readily available, so it’s not clear why it took so long to release these mandatory reports.

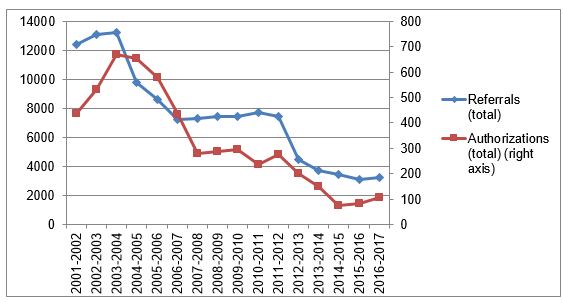

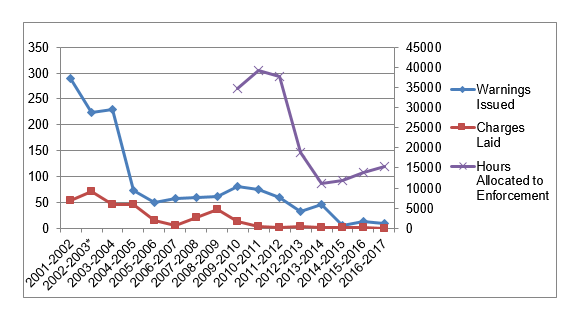

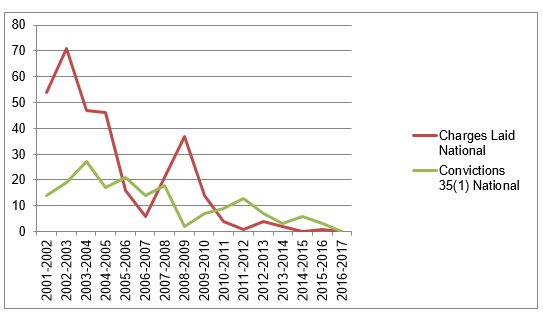

When added to previous efforts assessing the implementation and enforcement of the habitat protection provisions of the Fisheries Act, the numbers from these most recent reports confirm that the federal government virtually abandoned the habitat protection field in 2012 (following an already significant retreat around 2004/05) and has yet to re-establish its presence in any substantial way:

Figure 1: Number of Habitat Referrals and Section 35 Authorizations (2001 – 2017)

Figure 2: Enforcement Activity: Warnings, Charges, and Hours Allocated (2001 – 2017)

Figure 3: Enforcement Activity: Charges and Convictions

The new figures from these reports confirm how exceptional the R. v. French conviction was – recording an astonishing lack of prosecutions for habitat damage across the entire country, with only one charge laid over a three-year period (2014 – 2017). Presumably the conviction in R. v. French will be recorded in a future annual report. In contrast, in 2001, there were 54 charges and 14 convictions for violating the Fisheries Act’s prohibition on causing HADD.

Improving access to enforcement information

Access to information about enforcement should soon be improving. The recent amendments to the Fisheries Act also include a new public registry which the government could use to make available records of all charges, convictions and reasons for judgments for offences under the Act.

Unfortunately, the new public registry provisions do not actually require the valuable public information on Fisheries Act charges and convictions to be disclosed, even though they are public records. Fisheries and Oceans Canada has shown that it can make enforcement information available: it regularly publishes summaries of fishing penalties, forfeitures, prohibitions or orders from all regions of Canada related to the act of fishing, such as exceeding a daily catch limit or violating gear or timing restrictions.

Making enforcement information available on an ongoing basis through the registry would make it less problematic if and when annual reports are filed late (although we reiterate our concern that these reports should be tabled in a timely manner).

We urge the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans Canada to ensure that records of court cases, including reasons for judgment, and other data related to enforcement be included in the registry. The amended Act gives the Minister the power to “determine the form of the registry, how it is to be kept and how access to it is to be provided.” (s.42.4)

Prosecutions are an important tool

Prosecution is not always appropriate. Warnings and education are also important tools for compliance and enforcement. The DFO reports to Parliament make this point, outlining the three pillars of its National Compliance Framework:

- Pillar 1: Education, Shared Stewardship and Stakeholder Engagement includes informal and formal education programs and co-management/ partnership agreements. Compliance Education, Stewardship & Stakeholder Engagement Monitoring, Control & Surveillance Major Case & Special Investigations

- Pillar 2: Monitoring, Control and Surveillance includes activities such as land, sea and air patrols, inspections and compliance monitoring of third-party service providers, and enforcement response to non-compliance.

- Pillar 3: Major Cases/Special Investigations includes formal intelligence gathering and analysis, forensic audits and prosecutions.

Sometimes, however, prosecution is the best option, as shown in the Alberta case described above. When a warning doesn’t convince an offender to stop, a conviction coupled with a hefty fine just might. Publicity about enforcement serves as a general deterrent to other potential violators. Even though many fish habitat prosecutions are unsuccessful, they still send a strong signal to those carrying out activities in fish habitat that prosecution is a risk. The threat of convictions and fines also warn potential violators that their actions carry consequences. Without convictions and fines, the strength of the Fisheries Act protection for fish habitat is seriously diminished.

A new law for Canada’s fish

Protecting the habitat of fish and endangered species is a challenging job, and regulators, investigators and enforcement officers need effective legal tools to do their job. They also need political direction to make full use of the tools at their disposal.

For more than 40 years the Fisheries Act protected fish habitat broadly against harmful alteration, disturbance or destruction. Court decisions over those decades established a body of law about what one expert characterized as the “historic effectiveness” of the “very vigorous environmental protection element” of the fish habitat protection regime of the Fisheries Act.”

With the recent amendments – which restored the the prohibition on causing Harmful Alteration, Disturbance, or Destruction (HADD) of fish habitat using the exact same language as what was in place prior to 2012 – Canadians can take comfort in the fact that our Fisheries Act is once again strengthened, providing broad protection for fish habitat throughout Canada’s oceans, lakes, rivers and streams. But the strength of this protection is also dependent on adequate implementation and enforcement, which itself is contingent on transparency (such as Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s annual reports to Parliament). In other words, the restoration of the habitat protection provisions was a necessary, but not sufficient, first step; enforcement and transparency are the other key factors in ensuring adequate habitat protection. And on this front, we still have a very long way to go.

(Caveat: most of the new law, including the amendments described in this post, will only come into force at a later date to be determined by Cabinet.)

Photo credit: W. Writer