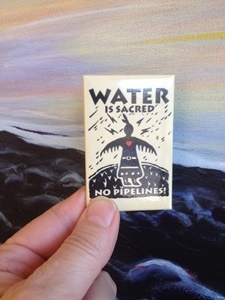

The words on this button have become my mantra: “Water Is Sacred. No Pipelines.” Isaac Murdoch’s image of Thunderwoman – the same image we see on social media, at Standing Rock, at protests encouraging divestment – is doodled into my notebook, on my calendar and emblazoned on my hoodie.

These simple and profound words, “Water is Sacred,” have become a call to action in North Dakota where, since April 2016, thousands of people have come together to protect water from “the Black Snake,” the oil pipeline proposed to bring oil under the Missouri River. People continue to come together proclaiming Mni Wiconi, “Water is Life.”

Over the summer and currently, despite the presence of thousands of people, the story has been under-reported, except for the coverage of independent news organizations. Corporate media did their best to maintain a news blackout, maybe because corporate media is aligned with Big Oil and Big Money. Despite newsworthy events (such as a woman’s arm being blown off, or the use of water cannons and attack dogs, or the arrests of hundreds of people), over the summer the story was strategically ignored.

I do my best to counter this silence by wearing a conversation-starter Thunderwoman button – and I take seriously the advice of Neil Young to “share the news.” At every opportunity, in the lineup at the grocery store, in the ferry waiting room, and through art, I remind people there’s yet another “battle raging on sacred land” and about how “our brothers and sisters had to take a stand.”

I’ve come to understand that issues like pipelines and water are connected to social and economic justice, and how there can be no justice on stolen land. It's all connected.

Having been part of the RELAW project (Revitalizing Indigenous Law for Land, Air and Water) since January 2016, during the past year I’ve had a sharpening of this focus of connection and intersectionality. Through this project, participating Indigenous nations work with community researchers and lawyers to develop legal instruments grounded in their traditional laws, to apply to the environmental issues they’re facing today.

Along with my WCEL colleagues and community participants of the RELAW project, I’ve immersed myself in Indigenous stories and have considered other worldviews, values, and cultural assumptions. I’ve thought about relationships and responsibilities, obligations towards the environment, and the consequences of not following legitimate processes for decision-making. My thoughts and perspectives have shifted, as though I'm seeing the planet through a different (and interconnected) lens.

Early on in the RELAW project, I prepared for my work with the Tsawout First Nation by reading the work of young Tsawout lawyer Rob Clifford. I learned that the first WSÁNEĆ man was placed on the Earth in the form of rain, and that he worked alongside the Creator to assist in shaping the world with mountains, rivers and lakes, helping things grow and bringing life. He was rewarded for his good work with the gift of a wife. I learned about mutual responsibilities in caring for land and water.

While on the ferry travelling home, I considered my own relationship to water and I thought about how that relationship would be different if I'd grown up hearing these stories that portray water as a relative, a beloved grandfather, a gift from the Creator deserving of respect and care.

And during this same time period, I heard of the approvals of the Enbridge Line 3 and Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain pipelines, the Petronas LNG terminal on Lelu Island, and the ongoing federal permit approvals for the Site C dam – all of which seem antithetical to the principles of relationality and responsibilities to care for land and water. I’ve developed a sense of urgency, a feeling that we can't do our RELAW work fast enough – particularly in recent months as our southern neighbours’ approach on issues of social and environmental justice has taken a sharp turn in the wrong direction.

Because of all the other work that goes on here at West Coast Environmental Law, and the conversations I become part of, this is what has happened to my psyche: I see connections between everything. When on a daily basis I think about things like pipelines, dams, and global warming, I notice the slender thread upon which everything hangs, that moment between normalcy and catastrophe, when everything could unravel. When, because of climate change, the flooding in Louisiana becomes connected to the fires in Fort Mac, and corporate capitalism means the fish farms in Musgmagw Dzawada’enuwx territory are connected to garment workers dying in factory fires and, in my mind, everything is connected to Site C.

There can be no justice on stolen land. Or on (or with) stolen water.

Last month in sub-zero temperatures, water protectors in North Dakota were sprayed with water cannons, meaning the Creator’s gift was used in a despicable and cruel way.

Similarly, the Site C dam will use the sacred gift of water in destructive ways, in ways for which it was never intended by the Creator. This precious gift, water from the Peace River, will be used to destroy fish and moose habitat, and good farmland with all that alluvial soil, turning a beautiful river valley into a sacrifice zone. Only a Trickster would take a sacred gift and abuse it to do something so stupid and destructive.

This week I remembered an experience from years ago, travelling with Snuneymuxw Elder Kwulasulwut, Dr. Ellen Rice White. We’d spent a few days travelling and staying together in a hotel, so we had many conversations and were developing a rapport.

As we drove past a particular patch of grass on the side of the road, Aunty Ellen pointed to it and told me her grandmother was a weaver and could speak to and understand the language of grass. She paused and then turned to me and said, “I’m telling you this because your grandmother could do this too.”

Apparently my Kwakiutl grandfather (with whom Aunty Ellen had been acquainted) had told her that his mother, my great-grandmother, also communicated with grass. It seemed as though Aunty Ellen had waited for this particular moment, for a time when we were close enough, deep enough in our conversations, that she trusted me with this information. This, too, has been a recurring theme in our RELAW work: there is a right time and place to tell stories.

Later, when I dropped her off at her house and we were saying good-bye, Aunty Ellen invited me to stop in when I was passing through Nanaimo. She suggested I come for a glass of water.

While other people might have extended an invitation to drop by for coffee or tea, Aunty Ellen was offering a simple glass of water. At the time I thought this invitation was cute, or maybe a reflection of her age or lack of mobility.

Now, after a year of RELAW and reflecting deeply on my own relationship and responsibilities to water, I see Aunty Ellen’s offering differently. Maybe from her perspective as someone who grew up immersed in stories of the preciousness and sacredness of water, she was offering me the very stuff of life, something akin to medicine, a precious gift from the Creator.

More than ever, we could all use more of this perspective. The planet needs it.

Mni Wiconi: Water is Life.

By Maxine Hayman Matilpi, RELAW Project Lead

We are now seeking Expressions of Interest from Indigenous nations to become part of our second cohort for the RELAW project. Expressions of Interest must be sent by email to Maxine_Matilpi@wcel.org before Friday, March 17, 2017.