Prevention of environmental damage is always better than response and clean-up. This became very obvious to residents in Metro Vancouver in 2015, when a cargo ship, the MV Marathassa, spilled 2,700 litres of fuel into the waters of English Bay.

Yet the recent dismissal of all charges against the vessel show that the lessons from one of the most devastating spills in history, the Exxon Valdez, have yet to be fully absorbed in Canada.

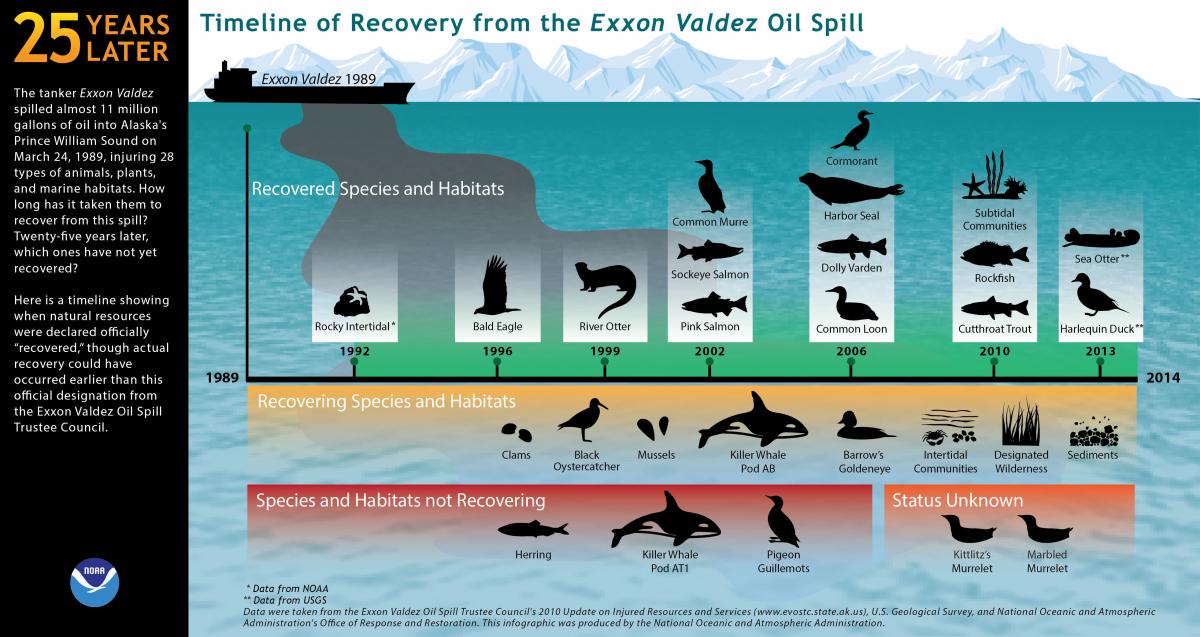

This week marks the 30th anniversary of the Exxon Valdez oil spill. On March 24th, 1989, the T/V Exxon Valdez ran around in Prince William Sound, Alaska, spilling almost 11 million gallons of oil into the pristine waters of the Sound. Impacts to wildlife from the oil were devastating; orca populations, sea otters, seals, sea birds, and many other marine species suffered in the weeks and months following the spill.

While scientists anticipated these immediate impacts, the long term impacts of the spill were unexpected and unprecedented. Today a few thousand gallons of oil, nearly as toxic as the day it was spilled, remain trapped on the shorelines of Prince William Sound.

Wildlife populations and species have taken longer to recover from the spill than anticipated. Three decades on, some populations have yet to recover to their pre-spill numbers, in part due to the persistence of oil in the environment causing chronic impacts to animals like sea otters, and accumulation of oil hydrocarbons within food webs.

Timeline graphic courtesy of US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA).

The Exxon Valdez changed our understanding of the long-term consequences of oil spills both for the marine environment and for people. It also persists as a reminder of the real and increasing threat of oil spills on the BC coast, while Canada’s laws struggle to catch up.

The response to the 2015 MV Marathassa spill highlight the inadequacy of Canada’s regulatory framework to address and respond to oil spills. Despite the perfect April weather conditions and the spill’s close proximity to Vancouver in the middle of English Bay, it took four and a half hours for the responsible body to begin deploying booms to contain the 2,700 litres of oil released by the spill. The delays and miscommunication were the subject of an independent review.

The 2015 Marathassa spill was followed by the even larger Nathan E Stewart spill near Bella Bella in 2016, which leaked 110,000 litres of diesel fuel into the ocean in Heiltsuk territory. Heiltsuk First Nation’s clam harvesting has been suspended ever since, and the nation has filed a lawsuit against the provincial and federal governments, as well as the ship owner.

The risk of spill incidents would only increase if the Trans Mountain pipeline and tanker project goes ahead. In recognition of this increased concern, the BC government is also exploring policy options to apply its spill response powers in the marine environment, a process which WCEL has participated in.

A disappointing series of court decisions

In a series of decisions in 2018 and 2019, the MV Marathassa and its operator, Alassia NewShips Management Inc., were charged with 10 environmental offences under numerous federal laws: the Canada Shipping Act, 2001, the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, the Fisheries Act, and the Migratory Birds Convention Act. The court acquitted the Marathassa on all counts, while Alassia NewShips Management, a Greek company, has refused to acknowledge BC’s jurisdiction and has not appeared in court.

The Crown appealed both decisions to the BC Supreme Court, but decided to abandon the appeal just this week.

This disappointing case points to several weaknesses in Canada’s regulatory framework for marine spills:

- First, the court decided that the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA) only prohibits the deliberate or intentional release of oil or other substances into the ocean – the Act does not apply to accidental spills.

- Second, the court halted charges under the Fisheries Act for reasons that have not been publicized.

- Third, the court found that the Marathassa and its crew followed all safety and operational regulations, and that the defects to the vessel that caused the spill were unforeseeable. It was for this reason that the court acquitted the Marathassa of charges under the Canada Shipping Act and the Migratory Birds Convention Act.

Most telling was the court’s finding that the cause of the spill was unforeseeable – a key reason for its acquittal of the vessel.

“The hazards...were not foreseeable. The Marathassa, the crew and Transport Canada all expected that the brand new vessel would be free of those defects.” (para 265 of February 2019 decision)

But spills are never unforeseeable; they are an expected part of business. After the Exxon Valdez spill in 1989, Canada appointed a Public Review Panel on Tanker Safety and Marine Spills Response Capability, which concluded that a catastrophic marine oil spill can be expected once every fifteen years in Canadian waters, and a major spill can be expected at least once a year.

Who bears the cost of spills?

The MV Marathassa case highlights the weaknesses of Canada’s legal system when it comes to prosecuting oil spills. But laying charges for violating Canadian laws is just one way of attributing responsibility for the social and environmental harms that spills cause. Another way to ensure accountability is to hold companies liable for their pollution – according to the “polluter pays” principle, which exists in Canada under the Marine Liability Act.

Under the current regime, Transport Canada says ship owners are held liable for costs associated with spills, and all vessels must have insurance for oil spill damages. Companies are also required to pay into a Ship Source Oil Pollution Fund maintained by the federal government, which is intended to compensate communities, businesses and taxpayers when the costs are too high to be covered by the ship owner (or when the source of the spill is unknown).

But in the case of the MV Marathassa, the City of Vancouver waited years for compensation for clean-up. In the meantime, taxpayers are left holding the bag.

In the wake of the Exxon Valdez spill, over $2 billion was spent on clean-up, but only 14% of the oil was ever recovered. American scientists estimate that 0.25% of the original spill remains trapped in the beaches and coastline of Prince William Sound. This recovery rate is standard for marine spills: international experts say that clean-up efforts for on-water oil spills typically only recover 10-15% of the spilled oil.

And people still feel the long-term consequences of the clean-up. The livelihoods of more than 32,000 people were affected through damage to tourism and commercial fishing. Many workers involved in the clean-up developed liver, kidney, lung and nervous system disorders. A coalition of environmental organizations in the United States is now suing the Environmental Protection Agency over the use of chemical dispersants in cleaning up oil spills, which they say form substances that are more toxic to animals and humans than the spill itself.

What we’ve learned from Exxon Valdez

Though spill response will always be important, the public remains vulnerable to oil spills. That’s why it’s so important to prevent spills from happening in the first place. The federal government has taken steps towards spill prevention by tabling Bill C-48, the Oil Tanker Moratorium Act, which would prohibit oil tankers carrying more than 12,500 metric tons of crude oil or persistent oil from stopping or unloading in ports along British Columbia’s north coast .

We can look to other jurisdictions for ideas on spill prevention as well. For instance, the Marine Exchange of Alaska is a non-profit organization that tracks shipping vessels and receives alerts when they start to go off-track – either preventing spills outright, or activating response measures far more quickly than current systems.

Lastly, we can look to solutions that will internalize the cost of spills within the industry – by increasing liability for spills and environmental damage, and fixing regulatory weaknesses that let companies off the hook. The goal is not to charge more companies with regulatory offences, but for those same companies to take responsibility for doing absolutely everything to prevent a spill, and to take responsibility for cleaning up their mess.

Thirty years later, it’s time to act on the lessons from the Exxon Valdez spill. Pollution prevention pays off.