BC fisheries are struggling with declining stocks due to ever-increasing pressures from climate change, coastal development, pollution and industrial fishing. But we need only look to Indigenous leadership for solutions.

Indigenous peoples on the Pacific coast have sustainably managed and stewarded the lands and waters for millennia. Indigenous nations had and continue to have sophisticated laws and governance systems in place to ensure fisheries are healthy enough to sustain future generations. It is only over the last 150 years, since the Canadian federal government imposed colonial fisheries management laws that deliberately suppressed Indigenous governance, that stocks have declined to the point of collapse.

Indigenous harvesting techniques, many of which were made illegal by the Canadian government, are proven to work, while also ensuring there is enough for everyone. In fact, there are numerous examples of Indigenous fisheries that sustainably harvested more than modern day fisheries: for instance, researchers have found that the lowest Indigenous harvest of Pacific salmon prior to European contact (88 million kg/year) was still higher than the average harvest under Canadian government’s management since the 1980s (70 million kg/year). These numbers speak for themselves.

The lowest Indigenous harvest pre-contact (88 million kg per year) was still higher than the average harvest under DFO management since the 1980s (70 million kg per year).

Excluding Indigenous nations from marine governance has devastating impacts

The systematic and centuries-long exclusion of Indigenous nations from ecosystems management, and particularly in the marine context, has had serious cultural, social, ecological and economic impacts.

For example, the Pacific salmon fishery has declined significantly over the past several generations. Salmon are an integral part of Coastal First Nations’ identity and way of life, and have been central to their economies since long before European settlers arrived. Research from Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance (CCIRA) shows that sockeye salmon stocks have declined 90% since 1950, and chum stocks have declined 94% since 1954. Just last year Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) closed 60% of the commercial salmon fishery in an attempt to “give salmon a fighting chance at survival.” This has had devastating impacts to fishers, Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike.

Colonial-style fisheries management and conservation has demonstrably failed. In contrast, areas managed or co-managed by Indigenous peoples have higher biodiversity than areas that do not involve Indigenous management, even surpassing the biodiversity found in most parks or protected areas.

As Christine Smith-Martin, the Executive Director of the Coastal First Nations-Great Bear Initiative said in the context of fisheries management:

…the problem with fisheries management over the past century has been not just a matter of unsustainable extraction practices that have taken more from the sea than could ever be replenished. It’s also that decision-making power and control were taken from First Nations – the people with the most to lose if sustainability is overlooked.

Fortunately, a solution to the problem is clear. Rebuilding fisheries requires a revitalization of Indigenous governance, including Indigenous fishing techniques; and Crown governments holding up their commitments to reconciliation by respecting Indigenous governance and entering into meaningful co-governance arrangements.

Recognizing Indigenous governance and leadership is essential

Encouragingly, Indigenous nations are reasserting their right to govern their lands and waters – and are having success. Spencer Greening, a doctoral researcher, hunter and angler of mixed Tsimshian and European descent, states in a February 2020 article for the Anchored Outdoors website that:

the success and maintenance of diverse and healthy species among Indigenous peoples is not because we have stopped hunting and fishing. It is the way we hunt and fish that can allow ecosystems to thrive.

Below are four examples of Indigenous fisheries management that have resulted in positive outcomes for ecosystems, and for the humans that rely on them. These are just four of countless examples – stories of this type are being released almost daily and even those are just a fraction of all the exciting work happening on the ground.

Selective harvesting: Fish weirs in Comox Harbour (K’omoks First Nation) & Central Coast (Heiltsuk Nation)

One example of sustainable fisheries management is the use of fish weirs, or traps. They are among several Indigenous fishing technologies that allow for selective harvest – including fishwheels and dip nets – and that were destroyed and banned by the Canadian government after colonization.

In 2003, a network of fish weirs was unearthed in the Comox Harbour on the east side of Vancouver Island. The weirs are essentially wooden posts arranged in heart-shaped or chevron patterns that trap fish who are seeking shallows when the tide is in, so they cannot escape as the tide recedes. The ancestors of the K’omoks First Nation used these weirs between about 1,300 and 100 years ago and they allowed the harvesters to assess the strength of the salmon return and adjust their harvest in response. The traps acted as ponds to keep the fish alive until harvesters collected them, allowing fishers to take only what they needed and release the rest back to the ocean.

This practice was banned in the early 20th century as the federal Crown government attempted to develop commercial fishing; this, combined with the intergenerational knowledge transfer that was prevented by the residential school system and other forced assimilation policies, resulted in fish weirs’ use fading away.

In 2013, however, the Heiltsuk Nation initiated a four-year research project in Koeye River on the Central Coast in which fish weirs were used to count and tag returning sockeye salmon. This was in order to revitalize weir building in the community and inform adaptive local management of the fishery. Since the project’s inception, the Nation has had interest from other Indigenous nations, who have visited the site to learn from the research.

Spawn-on-kelp and proactive governance: Herring fishery management in Haida Gwaii (Haida Nation)

Herring is central to coastal Indigenous nations’ culture, traditions and way of life, and the archaeological record – in combination with local and traditional knowledge – confirms the existence of previously abundant herring fisheries. Stocks have declined significantly over the last century due in part to the contemporary approach of using a “kill fishery” to commercially harvest roe or herring eggs (in which the herring are killed before they spawn), often with fishery openings of only a few hours at a time. Indeed, the fishery was completely closed in British Columbia between 1969 and 1972 due to stock collapse, and different regions have been variously closed since.

The kill fishery is in contrast to the spawn-on-kelp method used by the Haida Nation and other coastal Indigenous nations. This method involves suspending weighted kelp from lines in spawning areas. The herring lay their eggs on the kelp, and then the eggs are harvested while the fish swim free.

In 2014, after more than a decade of sporadic closures – and despite DFO staff recommending against it due to low stocks – the Minister of Fisheries re-opened the Haida Gwaii commercial herring fishery. However, the Haida reached an agreement with commercial fishers to not fish in the area.

In 2015, DFO proposed opening the fishery again, and the Haida again exercised jurisdiction. They wrote an open letter to all commercial fishers requesting they do not select Haida Gwaii as their fishing area. The United Fishermen and Allied Workers Union supported the request and sent a similar letter to all commercial fishers, which stated that the Union based its support of the Haida on “[an] independent science review of the herring stocks in the regions, the lack of inclusive decision-making; our own fishermen’s assessment of the state of these stocks; respect for the local First Nations insights; and willingness to build a collaborative understanding of the state of the herring in our shared ecosystem.”

By and large, local fishers were respectful of the Haida’s authority and complied; only two licence holders selected Haida Gwaii. The Council of the Haida Nation (CHN) also went to court to challenge the reopening. The Federal Court found in favour of the Haida and granted an injunction prohibiting DFO from opening the Haida Gwaii herring fishery.

This case is one of a number of cases in recent years where Indigenous peoples have used their constitutionally-protected Aboriginal rights as a basis to challenge DFO decision-making (see for example, a successful motion by the Ahousaht, Ehattesaht, Hesquiaht, Mowachaht/Muchalaht and Tla-o-qui-aht to prohibit the opening of a commercial herring fishery on the West Coast of Vancouver Island because of their conservation concerns).

In December 2015, DFO announced that there would be no 2016 commercial herring fishery in Haida Gwaii waters, and this has continued each year until the present. The Haida Nation’s governance has been absolutely crucial in preventing a stock collapse by managing the herring population in the area.

Enforcement and co-governance: Herring fishery management on the Central Coast (Heiltsuk Nation)

The Heiltsuk, located on the Central Coast around the town of Bella Bella, have harvested herring products for approximately 2,500 years. They manage the herring fishery and spawn-on-kelp fishery by restricting access to harvest zones defined by kinship systems.

When DFO opened the Central Coast commercial herring fishery in 2014, the Heiltsuk – like the Haida – objected. After raising concerns with DFO, the Heiltsuk enforced their own laws by escorting commercial boats out of the area and blockading the local DFO office.

In 2016, after meetings with DFO came to an impasse, the Heiltsuk worked directly with commercial fishers on fisheries management, culminating in the Herring Management Plan – which ultimately was signed by DFO and the Heiltsuk First Nation. The terms of the Plan include no-go zones designated by the Heiltsuk, a smaller catch, prohibition of the night fishery, and incorporation of Heiltsuk knowledge into the management plan. These measures put in place to address the Heiltsuk’s conservation concerns also illustrate Heiltsuk ğvi̓las (law) and traditional fisheries management practices.

Indigenous nations asserting their authority to govern can and has led to co-governance arrangements that are much stronger than those that exclude Indigenous peoples.

Fishery closures and enforcement: Crab fishery management on the Central Coast (Kitasoo/Xai’xais, Heiltsuk, Nuxalk, and Wuikinuxv Nations)

Since 2007, Central Coast Nations have formally expressed concerns to DFO about declining food, social, and ceremonial (“FSC”) catch rates for a variety of species, including Dungeness crab. FSC rights are held by Indigenous people and recognized under Canada’s Constitution; the Courts have defined a hierarchy of fishing priorities, with conservation coming first, followed by the FSC fishery, and then the commercial and recreational fishery.

In 2014, the Kitasoo/Xai’xais, Heiltsuk, Nuxalk, and Wuikinuxv proposed a network of Dungeness crab closure areas to combat declining stocks and meet conservation and community needs. The Nations declared the closures under their laws, and shared the notice of closures with DFO; DFO denied the necessity for closure areas, citing a lack of evidence.

In response, the Nations and collaborating scientists developed – and raised money to fund – an experiment to examine fishery effects on crab populations. The experiment involved comparing open sites to closed areas (which were particularly important for FSC fisheries and acted as the control groups that measured the effect of harvest pressure). The nations used Indigenous knowledge to select which sites should be open, and which should be closed.

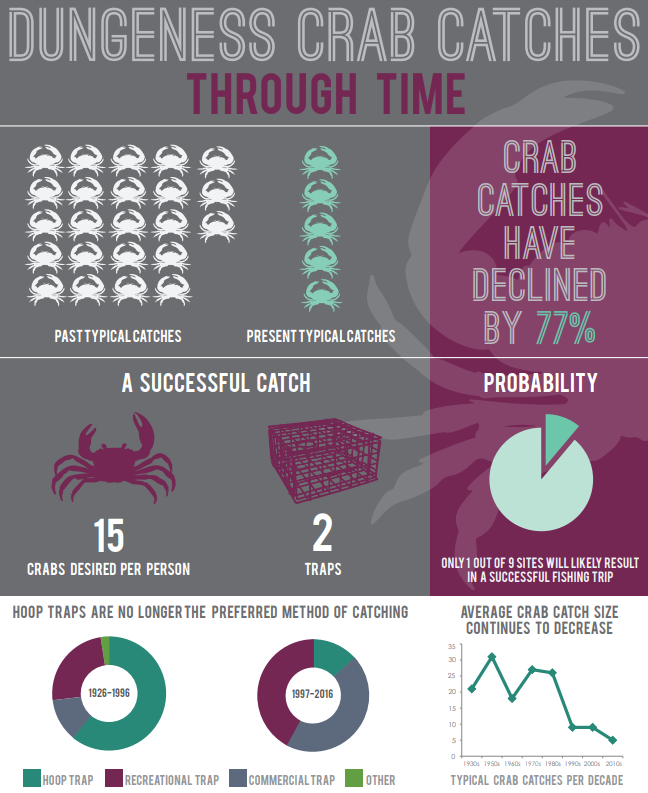

The results from the study, published in Global Ecology and Conservation, showed that the closures significantly benefited the crab population: both the body size and the numbers of Dungeness crab increased at the closed sites. Meanwhile, at sites open to commercial fishing, the size and population of crabs decreased.

Dungeness crab catches through time. Research was a partnership among the Heiltsuk, Kitasoo/Xai’xais, Nuxalk, and Wuikinuxv Nations, the Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance, and the University of Victoria’s School of Environmental Studies. Used with permission.

The Nations attempted to negotiate with DFO to have the closures imposed under Canadian law, but DFO chose not to recognize or communicate these closures. The Nations then asked commercial and recreational fishers directly for compliance with the closures (through contacts during patrols and posting notices throughout the communities). Compliance with the closures was high, in part because the closures were reasonably sized and located.

Members of the Nations also conducted regular patrols as part of the Guardian Watchmen program, an Indigenous monitoring, stewardship and enforcement program. Though initially there were conflicts between DFO and the Kitasoo/Xai’xais, as DFO did not respect the Nation’s authority to enforce closures under Indigenous law, ultimately DFO recognized the closed areas in its 2018/2019 Integrated Fisheries Management Plan (“IFMP”) for Crab by Trap fishing.

Then, in March 2021 DFO and the four Nations made a co-management decision to close the commercial and recreational fisheries in the area indefinitely, to ensure an FSC fishery can be maintained.

This story demonstrates the value of Indigenous management. The study cited above “provided evidence that fishery closures declared under Indigenous law – effectively social agreements between First Nations and the public without the benefit of federal legislation – could solve a marine conservation problem, albeit temporarily.”

In some cases, commercial fishers have demonstrated they recognize and respect Indigenous nations’ jurisdiction and knowledge of the waters in their ancestral territory – this is shown by the Haida, Heiltsuk and Central Coast nations examples above.

A brighter future for the ocean

Clearly colonial-style fisheries management and conservation cannot be the only model if we are to restore biodiversity and combat the climate crisis. The economic well-being of coastal communities is inextricably linked to ocean health, and it has become clear we need Indigenous leadership in order to restore ecosystems and community wellbeing.

Indigenous nations are revitalizing and applying their own laws to steward and govern the land and waters. This blog highlights a few examples, and there are so many more. This stewardship has brought other user groups on board, as we have seen with industry respecting the nations’ authority in the examples above – and with the Canadian government following with co-management arrangements which incorporate Indigenous laws and knowledge.

But more is needed. As laid out by the First Nations Fisheries Council of British Columbia, Crown governments must: respect Indigenous governance and authority; support the full restoration of Indigenous peoples’ deep connections and integrated relationships with fisheries and aquatic ecosystems; ensure equal participation in the governance and management of lands, waters and resources; and ensure Indigenous people can enjoy the benefits of aquatic resources now and into the future. Centering Indigenous governance from the outset will benefit us all.

Top photo credit: Bureau of Land Management Oregon via Flickr Creative Commons