More and more Canadians are living in cities, and these days we’re spending a lot more time there. But we don’t have to escape the city to connect with nature.

From appreciating urban trees and pollinators to admiring starry night skies – there are many ways that we can feel gratitude for our lives as urban Earthlings. And as lawyers, we are looking at the way law, policy and individual stewardship can help our cities strengthen and maintain these urban nature connections for generations to come.

Live long and prosper, together: Urban trees and us

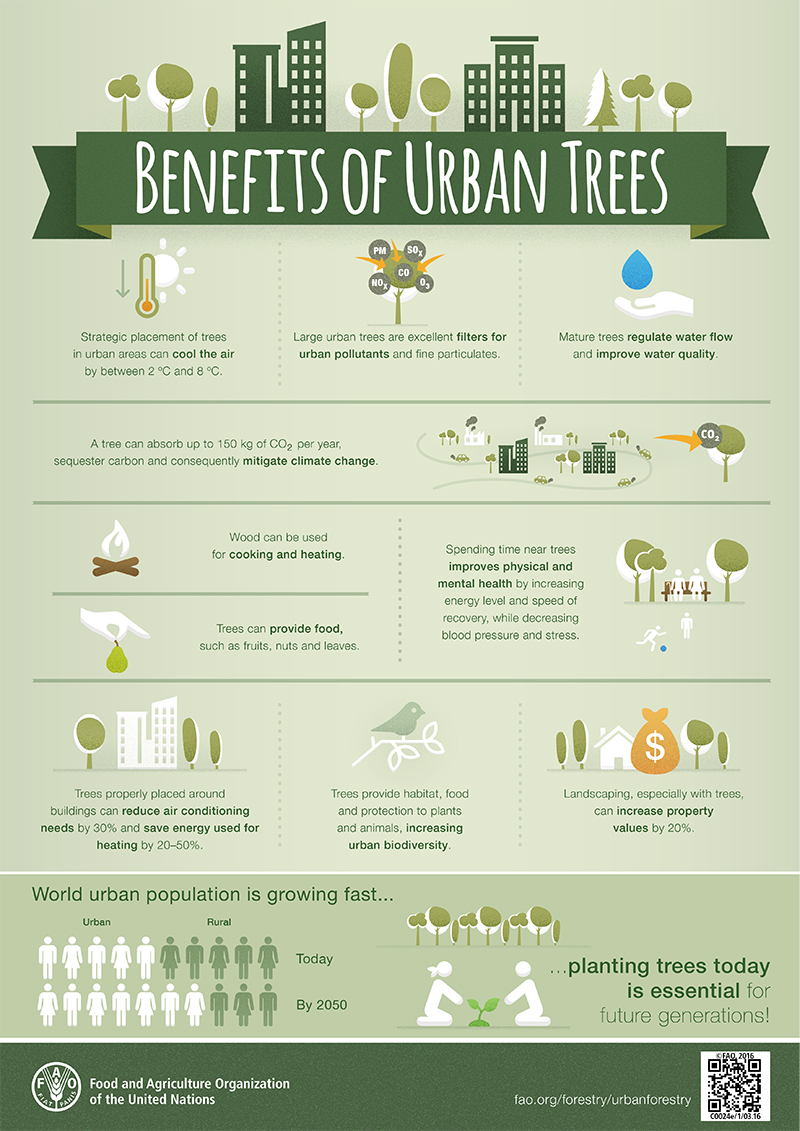

Trees are our urban friends, providing pleasant shade, nesting and perches for birds, a boost to air quality, and sometimes just a branch for a swing or a friendly trunk to lean on.

Mostly they are just there, quietly minding their own business – except for shedding leaves if they are deciduous, or sometimes shifting heavy sidewalks and parking spaces with their roots as a reminder of their silent, but prodigious activity. Still, we find their presence highly desirable, and having some trees in your neighbourhood not only increases property values but has been shown to improve your mental health.

If you had any doubts about how much city-dwellers love urban trees, you need only look to Melbourne. In 2015, the City of Melbourne set up email accounts for urban trees so people could report problems. Instead, people sent the trees thousands of love letters and existential questions.

Recently, cities have been putting in place ambitious programs to plant more trees, recognizing that they can also play an important role in managing rainfall with their canopies, and in supporting greenhouse gas reduction efforts by capturing and storing carbon. But as we start to talk about trees as essential “urban infrastructure” we are also learning more about their needs, and how to support them as a vital part of our communities.

New research sheds light on what trees need from us to flourish in what for them is a very challenging environment. If we help them get to maturity, they have a lot to offer, over several human generations!

Infographic by UN Food and Agriculture Organization

Trees need our help to grow

Urban trees and forests need help to thrive, and to build their resilience to climate change. They are vulnerable to climate impacts like shifts in temperature and precipitation, as well as increased attacks from parasites. Scientists are studying which types of trees will be suited to future climate conditions, and making recommendations about the types of trees that are appropriate for different places, projecting us decades into the future.

Yet, even where trees are well suited to their climate, planting trees is only the first step in nurturing them to maturity. Sadly, the current lifespan for many urban trees is very short – perhaps 50% are dead within 10 years of planting.

They might initially grow faster than their rural counterparts, possibly because they have access to more light and more carbon dioxide, but they have shorter lives, says a recent study that the researchers called “Live fast, die young.” This has a serious implication for urban tree planting policies and tree canopy objectives:

Removal of large trees for (re)development is often justified by replanting several seedlings in [their] place, but high mortality rates and the time required for a seedling to reach full stature can result in a sustained canopy decline for many years.

So why do urban trees fail to survive? There appear to be a variety of reasons, such as inadequate space for roots, damage to roots during construction and infrastructure repair, getting struck by cars, disease and vandalism. Providing adequate volumes of non-compacted soil so that roots can grow, irrigation, and key maintenance during the first decade seem to be effective in helping urban trees succeed.

Why mature trees are important

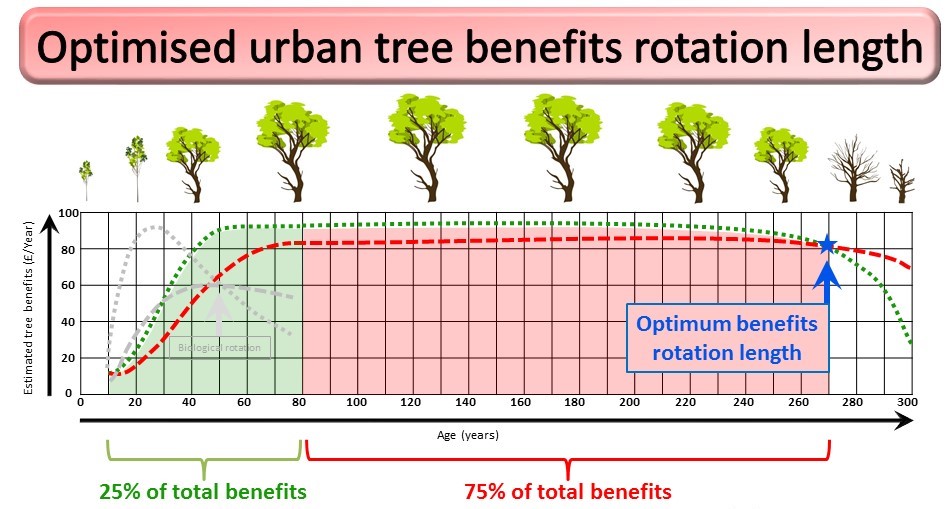

Mature, healthy trees are important members of our community. A recent study found that annual ecosystem benefits from trees (including air pollution removal, carbon sequestration and rainwater attenuation, but not including health and other benefits) hit their peak annual rate at around 50 years of age, and then can continue at that level for a hundred years or more.

Estimate of lifetime ecosystem benefits for urban trees in Sheffield City, UK. Prepared by Jeremy Barrell FICFor, 2017.

Healthy, mature trees can also provide climate resilience benefits for humans by helping to cool urban spaces in hotter summers (studies have shown that urban trees and forests provide measurable cooling of the air through evapotranspiration), addressing the urban “heat island” effect.

However, just getting to 50 years requires the careful planting and maintenance described above. This suggests that focussing on planting massive numbers of new trees doesn’t benefit us or the trees, if we aren’t also taking care of the mature trees that are already here. Instead of directing attention to planting huge numbers of saplings, we could think about maintaining a certain percentage of canopy cover, or maintaining an average age of trees in the 50 to 200-year range. As one expert has said, “we need trillions of leaves, not millions of trees.”

How do we protect the urban forest?

In BC, municipalities have broad legal powers under the Community Charter related to tree protection and cutting. They can protect trees on public property, but also on private property.

Despite the inherent challenges in attempting to regulate the way that people manage private property, a number of municipalities have recognized the importance of urban trees, and now have tree protection bylaws that apply to private as well as public properties, and restrict the ability of private owners to cut down mature trees. These bylaw powers are helping to protect the mature trees that provide maximum ecosystem benefits for our communities.

Local governments have other tools to grow and protect the urban forest canopy, as noted in the Kamloops Urban Forest Management Strategy. They can reinforce protection for urban tree canopies and mature trees in Official Community Plan policies and development permit requirements, and can use zoning bylaws to manage setbacks and landscape areas to promote tree canopy requirements. Specifications for new planting can incorporate recognized standards, and require supervision by qualified professionals such as landscape architects and arborists.

Many BC communities now have urban forest strategies that recognize the importance of the benefits provided by trees, and some communities have also made estimates about the significant value of services provided by trees. In Campbell River, it was estimated that street trees alone provide an average net benefit of $160,000 per year.

Despite the quantifiable benefits provided by urban trees, which are substantial (even if they likely only represent a portion of their true contributions), financing for maintenance and protection of urban trees remains challenging for local governments, because trees are not considered to be assets. Planting and maintenance show up as costs, but benefits don’t appear in municipal ledgers. Happily there has been discussion about amending the public sector accounting guidelines to include urban forests.

Federal funding opportunities for green infrastructure may yet provide opportunities for urban forest management, but to date there has not been a federal program targeted at urban trees and long-term urban forest strategies. “Shovel in the ground” approaches and performance criteria for more conventional infrastructure projects need to be rethought to fit the needs of living green infrastructure, including urban forests.

Whereas conventional infrastructure typically addresses one issue at a time (for example, pipes and drains for stormwater management), living green infrastructure often provides a bundle of benefits that might not be accounted for in a typical infrastructure grant. Making a shift to more natural, systems approaches in urban settings also can require more planning and design, and the integration of different types of expertise, as well as longer term maintenance and monitoring.

There is also a role for federal and provincial governments to play in providing supportive policy frameworks to allow financing options that access private funding, like green bonds and other instruments.

Let’s take a moment now to feel gratitude for the urban trees in our community – and also to the people, both paid and volunteer, who work to help them grow and be healthy. If you live in Vancouver, check out the Vancouver Tree Book, or you can search for other resources about the urban trees near you!

If you are a private property owner, your stewardship of the trees on your property is good for the whole community. We can all encourage our local governments to plan and manage their urban trees for the long term, and we can also ask federal and provincial policymakers to make urban forests part of the planning and funding for renewal of municipal infrastructure.

Small acts of kindness matter: Pollinators show us how

Pollinators don’t always get a lot of attention, especially in urban places. But they are here, working away, making important connections that help keep life vibrant in the city and even further afield. Bees, wasps, butterflies, hummingbirds, even bats – their delicate touch as they collect nectar from blossoms transfers genetic material from flower to flower, and allows plants to reproduce.

Bumblebee (Photo: Michael Whyte)

As it happens, pollinators like wild bees can do very well in urban landscapes, unlike some other threatened species. And it turns out that corresponding small-scale efforts by humans, at the level of backyards and community gardens, make a measurable, positive impact that may extend beyond urban boundaries. As researchers have said, “Pollinators put high‐priority and high‐impact urban conservation within reach.”

Instead of thinking about the city as, well, an urban wasteland, pollinators give city folks an opportunity to actively engage in conservation work with big benefits. While agricultural lands have become less diverse over time, urban areas still contain a relative diversity of habitats, with small pockets of vegetation where pesticide and herbicide use can be effectively restricted or eliminated.

This means that we can quite readily tweak measures that support green infrastructure to be beneficial for pollinators. A study in Chicago, for example, showed that if green roofs incorporate plant diversity and nesting places, they can be valuable habitat for bees.

Research also suggests that there can be value in considering connectivity among different neighbourhood gardens and green spaces, which can be coordinated to boost biodiversity at the local level. In Kelowna, the “Nectar Trail” was a project where homes, businesses and schools in the Mission neighbourhood all committed to have at least a 1-metre square garden of pollinator-friendly plants – together they created a 7.4-km network for bees and other industrious pollinators!

It’s also important to regulate and reduce the use of pesticides in a more comprehensive way. One class of pesticides, neonicotinoids, has been shown to be especially harmful to bees. Some municipalities, like the City of Vancouver, banned the use of this pesticide some years ago. After years of public pressure based on research and enforcement in other jurisdictions, the federal government has acted to restrict their use.

Action at the neighbourhood, backyard and balcony level is just as important. We can all make a difference for pollinators, and reach out to them as they do their careful and vital work.

Many BC communities have initiatives underway to protect and encourage pollinators, like the Island Pollinator Initiative, the Pollinator Project, and the Butterfly Project. The Pollination Ecology Lab at SFU has some helpful information for different places in BC about how to encourage pollinators in your community.

Hello darkness my old friend: Embrace the night sky!

Have you ever had the chance to view the night sky outside a city or town? The vast number of stars in the sky and the views of the Milky Way can be breathtaking.

Dark skies are rare in our cities and towns, where we have lit up the night, particularly along roads, in parking lots and in commercial areas. According to the “Bortle dark sky scale” – where 1 is the ideal dark sky and 9 is a fully-lit night sky – a typical city night sky view may be an 8 or a 9, with only the moon, the brightest stars and planets visible. You’ve heard of the Milky Way, but have you ever seen it?

City of Victoria lit up at night (Photo: Peter Nuksa)

It’s not just stargazers who are affected by nighttime light: there are health impacts for us and other species. The lack of darkness messes up our circadian rhythms, with possible links to many common diseases. Light at night creates confusion that may be fatal for wild species like migrating birds and sea turtles. Not to mention the energy that is consumed by all of those lights, and the climate consequences.

Still, as the US National Parks Service points out, unnatural encroachment on darkness is an environmental problem that we can address:

The loss of the night sky is unnecessary, and protecting dark skies doesn't mean throwing civilization back into the dark ages; it simply requires that outdoor lights be used judiciously, respecting our human environment, wildlife, and the night sky that we all enjoy.

To start, we can all do our small part by turning off unnecessary lights when they’re not needed, using only the amount of light that’s needed (how bright does your porch light really need to be?), and where it’s needed (is it pointed downwards?) Darksky.org has helpful information on how to reduce light pollution in your community.

To get at the largest night lighting sources, like roads and parking lots, experts agree there needs to be a shift in urban regulation and lighting standards.

Luckily, cities and lawmakers are rethinking urban lighting to reclaim the night sky. Let’s celebrate their work (and consider how to bring these solutions to our own communities):

- In Norway, “smart lighting” dims to 20% on quiet city roads, and goes to full lighting only when traffic passes by. It keeps residents safe, minimizes light pollution, and saves significantly on electricity costs.

- As part of its “Outdoor Lighting Strategy” the City of Vancouver made changes to its nuisance and building bylaws to reduce unnecessary lighting from buildings.

- The District of Saanich incorporated light pollution abatement regulations into its zoning bylaw to protect night sky viewing from the Dominion Astrophysical Laboratory.

- The Township of Langley has an “Exterior Lighting Impact Policy” that applies to new commercial and industrial developments, and is aimed at protecting dark skies, reducing energy consumption and wildlife impacts.

- In 2017 the State of New York enacted “Healthy, safe and energy efficient outdoor lighting” legislation, observing that “careful management of outdoor lighting is necessary to protect the health, safety, energy security, environment and general welfare of the people of the State.” The legislation encourages efficient lighting strategies, including “passive” lighting (such as reflective markers) where appropriate, and provides for the designation of “Dark Sky Preserves.”

Does your city or town have an urban lighting strategy that promotes healthy and efficient practices, and good doses of darkness? If not, send an email to your city councillors.

And, if you can, soak in some night sky. The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada has very useful information for stargazers. Even if we can’t see all the stars in the sky, we can still feel wonder at the tiny bits of starlight twinkling at us across the universe, and the mysterious and beautiful face of the moon.

Beautiful starry sky over Chilliwack, BC (Photo: Tyler Ingram)

So let’s celebrate the wonder of nature in our cities: hug a tree, plant a bee-friendly flower, and dim the lights in favour of some star-gazing! And consider getting involved in efforts for the long term protection of nature in our cities.

Happy Earth Day!