Cooperative actions to explore and protect the deep sea

Perhaps the best-known examples of cooperative marine governance agreements in Canada are in Haida territories on the north Pacific coast, where the exciting deep sea Northeast Pacific Seamounts Expedition just concluded.

Since 2007, the Council of the Haida Nation and Fisheries and Oceans Canada have cooperatively managed SGaan Kinghlas-Bowie Seamount Marine Protected Area (MPA). The two governments recently jointly agreed to close all bottom contact fishing at this MPA, whose Haida name means “Supernatural Being Looking Outward”.

The Haida Nation, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Oceana Canada and Ocean Networks Canada explored offshore seamounts at SGaan Kinghlas-Bowie Seamount MPA and at the Dellwood and Explorer Seamounts in the proposed new MPA called the Offshore Pacific Area of Interest. Video footage from the expedition shows the beauty of these underwater mountains, and highlights the value of collaborative work to study and protect these vulnerable ecosystems.

(Video Credit: Oceana Canada)

Upon the conclusion of their expedition last month, the Haida Nation called for restricting shipping traffic in the areas around SGaan Kinghlas-Bowie Seamount and Oceana called for permanent closure of all seamounts to bottom contact fishing.

Growing momentum for co-governance of marine areas

There is a shift underway toward true co-governance of marine areas in Canada. True co-governance exists where responsibility and authority for governing marine protected areas is equally shared between Crown and Indigenous governments.

This type of co-governance was a topic of discussion for the National Advisory Panel on MPA Standards, which wrapped up its hearings and submissions this July. The Panel will issue its interim report soon, aided by presentations from people across the country, including West Coast’s call for stress-free seas and implementation of true co-governance arrangements in both new and established marine protected areas.

This panel will make recommendations about “Indigenous approaches and governance with respect to marine conservation, including the evolving concept of IPCAs [Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas]”. The Panel can add to the momentum with recommendations for true co-governance.

Led by Indigenous action, several factors have also contributed to this rising change:

- The 2015 mandate letter for the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans committed to improving ocean co-management.

- The recent reports from a National Advisory Panel and the Indigenous Circle of Experts (ICE) provide recommendations to the government on advancing reconciliation through reaching Canada’s biodiversity conservation targets of protecting 17% of terrestrial areas and inland waters, and 10% of marine areas by 2020.

- The Parliamentary Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development unanimously recommended co-governance and a greater role for Indigenous partnerships within protected areas.

- An internal evaluation of the Oceans Protection Branch of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada in 2017 identified a lack of progress on the co-management commitment, and recommended developing a coordinated approach to co-management arrangements.

What is the future of marine co-governance in Canada? Four developments across Canada show that true co-governance arrangements are rapidly evolving.

1. Marine Managed Area for Nunatsiavut – Imappivut or “Our Waters”

Under the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement, the Nunatsiavut Government can create marine protected areas within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area. The Nunatsiavut Government has used this authority to propose a marine managed area that will cover the entire coastline of Nunatsiavut territory.

Under the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement, the Nunatsiavut Government can create marine protected areas within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area. The Nunatsiavut Government has used this authority to propose a marine managed area that will cover the entire coastline of Nunatsiavut territory.

They are currently developing a Nunatsiavut Marine Plan (called Imappivut or “Our Waters”) with the aim of fully implementing the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement in the entire coastal and marine waters of Nunatsiavut.

With this plan, they hope to guarantee that for generations to come, these waters will support a healthy marine ecosystem and prosperous Labrador Inuit. Though the governance structure for the area has yet to be finalized, in September 2017, the Nunatsiavut Inuit of Labrador and the Government of Canada signed a Statement of Intent related to marine space in Northern Labrador, which signals a move toward true co-governance of the area.

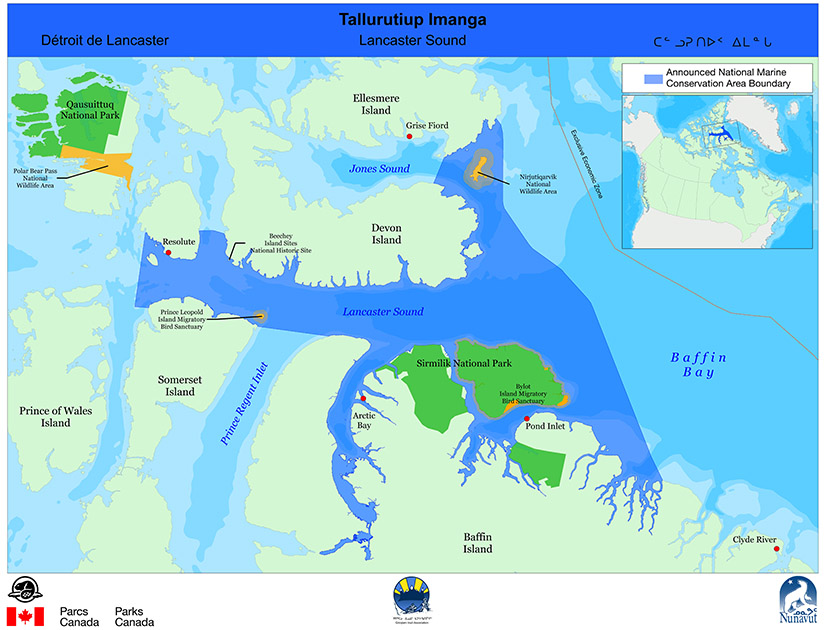

2. Talluritup Imanga – Canada’s largest protected area and a future model of Inuit-led marine governance?

The proposed protected area Talluritup Imanga, also known as Lancaster Sound, will become Canada’s largest protected area. The National Marine Conservation Area Reserve in Nunavut is home to about 3,500 Inuit, approximately 75% of the world’s narwhal population, 20% of Canadian belugas, the largest subpopulation of polar bears in Canada and some of the largest colonies of seabirds in the Arctic.

The governments of Nunavut, Canada and the Qikiqtani Inuit Association reached an agreement on the boundaries of the conservation area last year after the Inuit pressed for enlargement of the protected area boundaries.

The Inuit expect to negotiate full governance rights, and are in the process of deciding on an Impact and Benefits Agreement for the conservation area. The management plan and Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement need to be completed before the conservation area can be formally established. The National Marine Conservation Act requires consideration of traditional knowledge, and in this case Inuit Qauijimajatuqangit (Inuit traditional knowledge) will be an integral part of the management plan.

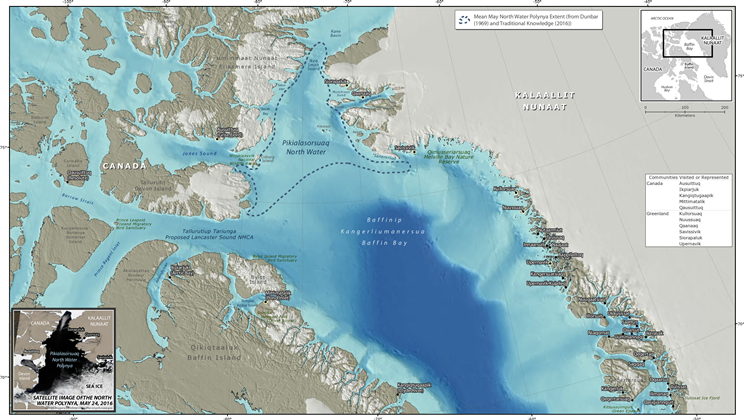

3. Pikialasorsuaq Commission on the North Water Polynya – Inuit-led transboundary MPA proposal

The Pikialasorsuaq (The North Water Polynya), or “The Great Upwelling”, is the largest polynya in the Arctic. Polynyas occur when ocean currents push up warm, nutrient-rich water from the deep towards the surface, maintaining an area of open water surrounded by sea ice throughout the year. It is one of the most productive regions within the Arctic Circle.

An exciting example of Indigenous-led protection has galvanized around this area, with the creation of the Pikialasorsuaq Commission, an Indigenous International Commission formed by the Inuit of Greenland and Canada. The Commission’s intention is to create a fully Inuit-governed marine protected area, and to allow free movement between both countries for Inuit peoples.

The Commission is led by three commissioners – one international Commissioner (from the Inuit Circumpolar Council); a Greenlandic Commissioner; and a Canadian Commissioner (from Nunavut).

NGOs such as Oceans North Canada and the WWF participated in the formation of the Commission.

4. Reconciliation Framework Agreement (RFA) – Coastal First Nations and Canada

A marine protected area network for the Northern Shelf Bioregion of British Columbia is being collaboratively developed by the Government of Canada, the Province of British Columbia and 17 First Nations.

A marine protected area network for the Northern Shelf Bioregion of British Columbia is being collaboratively developed by the Government of Canada, the Province of British Columbia and 17 First Nations.

On June 21, the Government of Canada and the Coastal First Nations signed the Reconciliation Framework Agreement for Bioregional Management and Oceans Protection.

The Agreement commits both parties to “coordinate ongoing efforts in the management and conservation of oceans, including marine spatial planning and developing a network of marine protected areas.”

It also affirms a shared commitment to emergency preparedness and increasing the response capacity of local First Nations.

The Agreement emphasizes the cultural and spiritual significance of the area to the Pacific North Coast Nations, as well as their reliance on the marine ecosystems and resources in the Northern Shelf Bioregion.

Moving forward

With crucial amendments to the Oceans Act set to be passed, making it easier to designate marine protected areas, it is time to focus on legislative changes for co-governance. While the four developments described here represent a growing shift towards marine co-governance across Canada, the federal laws used to establish marine protected areas are outdated, and do not acknowledge inherent Indigenous rights or provide a modern legislative framework to recognize a role for Indigenous nations in governing marine areas.

Both Indigenous legal orders and federal legal rules need to be at the heart of the reform of Canada’s protected area laws. The tide is turning, and all governments need to get on board.

(Top Photo Credit: Susan Clarke via Flikr)

(Nunatsiavut Map Credit: Inuit Land Claim Agreement/Nunatsiavut Government)

(Tallurutiup Imanga Map Credit: Parks Canada)

(Pikialasorsuaq Map Credit: Pikialasorsuaq Commission)

(PNCIMA Map Credit: PNCIMA Initiative)